The Durrells – ITV’s award–winning 2016 adaptation of Gerald Durrell’s bestselling trilogy about his family’s move to Corfu in the 1930s – was joyous and golden, awash with love, eccentricity and mad humour.

We all wanted to be part of that wonderful chaotic family as they moved from villa to villa – Strawberry Pink to Daffodil Yellow to Snow White – during their four-year stay. Lunching in the sun at a table half submerged in the Ionian Sea with Gerald’s brother and sisters Leslie and Margo. Drinking wine in the shade with his widowed mother Louisa (played by Keeley Hawes). Helping young Gerry himself tend his pelicans. Or maybe just being charmed by eldest brother, Larry, an aspiring writer who was portrayed (by Josh O’Connor) as tall, dark, charismatic and excitingly louche.

Of course, all writers exercise poetic licence, tidying up messy corners and smoothing over rough edges – particularly when writing about their own families.

But according to Larry – a new biography of Lawrence Durrell’s life, which was mostly written by the late Michael Haag and completed by his editor after his sudden death in 2020 – important chunks were edited out of the family story.

Such as the fact that Mrs Durrell was a raging alcoholic (as were all three sons) with depressive tendencies and delusions of grandeur who often took to her bed with a bottle of gin.

And that the Durrells were disliked in Corfu by many locals who found them rude, boorish and so disrespectful in their obsession with nude swimming and sunbathing that they were often stoned in a fury.

But perhaps the biggest surprise is Larry himself: the eldest brother who was feted as one of Britain’s greatest novelists after the publication of his exotic and erotic masterwork, The Alexandria Quartet, between 1957 and 1960.

Again, not all is as it seemed.

A new biography of Lawrence Durrell portrays him as bullying, manipulative, vain and violent

It turns out that, as well as being short – barely 5ft 2in – blond, thickset and a teeny bit piggy-looking with his bulbous nose and heavy brow, Larry was a boozy, womanising nightmare.

Bullying, manipulative, vain and violent, he left a trail of female destruction as he sailed through the Med (which he called the ‘sex organ of Europe’), carousing with bohemian writers Henry Miller and Anais Nin (who called him ‘pig-face’) and vowing never to return to the ‘shabby little island’ of his despised Great Britain.

Yes, he was fantastically charismatic in company – one friend claimed it was ‘as though someone had uncorked a bottle of vintage champagne’ when he entered the room – and was a loyal son and wonderfully attentive big brother. But, to women, he was deeply unpleasant.

He treated his first wife, artist Nancy Durrell (nee Myers) appallingly, shoving her down the stairs and refusing to let her stand next to any man who was taller than him. He was also deeply unkind to his second wife, Eve Cohen.

Perhaps it’s no coincidence that both struggled with mental health issues. As, apparently, did his two daughters: Penelope (Pinko) and the late Sappho.

When, in 1985, Sappho took her life at the age of 34 by hanging herself with a pair of tights in her north London home, it was reported that he didn’t even return to Britain for her sad, rain-soaked funeral.

And there’s more – though not covered in Haag’s book, which cuts off abruptly in 1945.

Because after Larry died in 1990 at the age of 78 in the South of France, a great sheaf of Sappho’s writings were finally released by her friend, literary executrix and former neighbour, Barbara Robson.

The Durrells – ITV ’s award–winning 2016 adaptation of Gerald Durrell’s bestselling trilogy – made us all want to be a part of that wonderful chaotic family, writes Jane Fryer

Viewers were particularly charmed by eldest brother Larry, an aspiring writer who was portrayed (by Josh O’Connor, pictured right) as tall, dark, charismatic and excitingly louche

In them, amongst many other claims, she accused her father of incest – her supposed memories set out in a particularly unpleasant poem which detailed the creases of his stomach and jowls during a summer siesta. But we’ll come back to that later.

Larry was born in India in 1912 to Louisa and her a successful civil engineer, whom he was named after. His was a seemingly idyllic childhood, awash with colour, servants, privilege and the fleeting glimpses of leopards. But it was all cut short when, aged 11, he was packed off ‘home’.

He loathed everything about Britain. The grey, suburban landscape; his school; his failure to get into Cambridge – all of which he blamed for his stunted growth. And it can’t have been easy.

His father died suddenly when he was 16, and Larry was notified by telegram and never really spoke of him again.

Louisa, was similarly off bounds. In one extraordinary interview with Malcolm Muggeridge for the BBC in 1965 – in which he expresses sexist, racist and misogynistic views and talks of putting women ‘on the slab’ – he says of his relationship with Louisa: ‘I will never go there. Too dark.’

Of course, both Larry’s upbringing and the era go some way to explaining his character, his temper and his loathing of English culture (which he called ‘the English Death’).

But there seems no excuse for his appalling treatment of women such as his first wife, Nancy Myers, whom he met in 1932.

She was at the famous Slade school of art in London, full of promise and a good five inches taller than him. He was working for an estate agent in Leytonstone.

Ironically, it was Larry’s vulnerability that first attracted her. According to Haag’s new biography, she said ‘he was gentle and small’ and liked to talk in a baby voice: ‘I’se only ickle baby… I’se only really teeny weeny.’

Together, they racketed about in London, playing jazz in clubs, running a photographic studio and partying: A period he described as ‘a dream of broken bottles, sputum, tinned food, rancid meat, urinals’.

Both were fuelled by a desire to live a different kind of life. To be creative and bohemian and have nothing to do with the dreariness of bourgeois life.

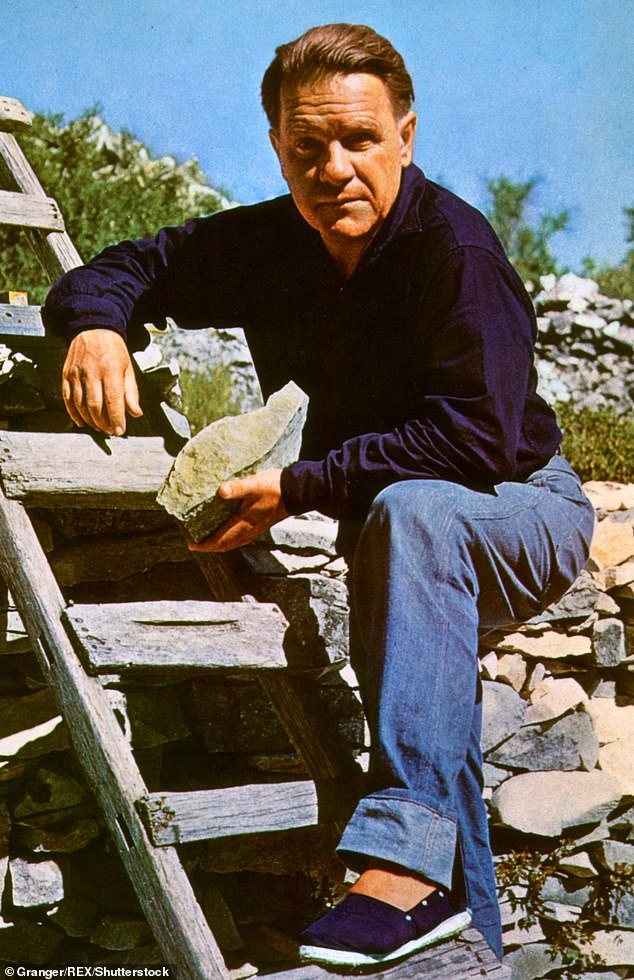

Lawrence Durrell pictured with friends in the ruins of Camirus, Rhodes, in September 1946

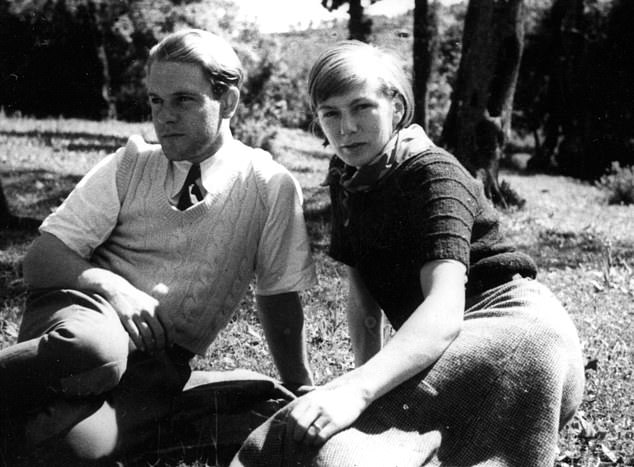

Larry and his first wife Nancy were the main drivers for the family’s move to Corfu – thanks to their shared desire to live a different kind of life

So it was Larry and Nancy – the latter completely erased from the Durrell family history – who were the main drivers for the move to Corfu. They would have gone alone, but Louisa was drinking so heavily, hallucinating about her dead husband and behaving so erratically that she couldn’t be left. So, they all went, along with Roger the dog.

In his 1954 book, Gerald wrote: ‘Our arrival in Corfu was like being born for the first time.’

Corfu was a happy place for the Durrells and, at the beginning, a paradise for Larry and Nancy who slept on the beach, drank, wrote, painted, quarrelled, made love, swam and sunbathed.

But, within a couple of years, it was falling apart.

Durrell treated her like dirt, called her a ‘dirty Jew’, and she became more withdrawn. In company, he’d either ignore her or humiliate her by snapping: ‘Why don’t you shut up?’

In 1938, he wrote to a friend, ‘Nancy wants to have a child, the slut.’

It wasn’t until 1945 – when Larry was stationed as a press attache in Cairo, and Nancy and their baby Penelope were in Jerusalem – that she mustered the courage to write and tell him she was leaving him. Penelope didn’t see her father again until she was in her teens.

Meanwhile, Larry threw himself into writing, his job at the Foreign Office, and women. They found him charming, charismatic and attractively dominant – despite his diminutive stature. He once described his third book, The Black Book, as ‘so good I am terrified of it’.

But he could also be funny, clever and wickedly good company. According to his fourth wife Ghislaine de Boysson, whom he married in 1973, he was still receiving ‘passionate letters’ from female fans well into his 60s.

After Nancy, his next big love was Eve Cohen, an Alexandrian Jewess, who was the inspiration for Justine in his famous Alexandria Quartet and whose heritage seemed to both intrigue and repel him.

When their daughter Sappho was born in 1951, after a long labour with her ‘head all scrunched up and eyes like slits’, Larry’s first comment was to joke that Eve must have been having an affair with a Korean.

Larry, his third wife Claude and daughter Sappho reading a newspaper together in March 1962. Sappho later accused her father of incest

But, while he was enchanted with his new daughter, Eve struggled with post–natal depression and was shipped off from their new home in Cyprus – where he was writing his travel book Bitter Lemons – to a clinic abroad. And so Granny Durrell stepped in to help but, having never seen the contents of a dirty nappy in her life, was horrified.

‘She said that when my mother came back, she was going to punish me,’ Sappho wrote.

Instead, when Eve finally returned in 1953, she found her daughter filthy and traumatised with matted hair. After a three-day stand-off, she scooped Sappho up and moved back to London where they lived in a succession of tiny flats.

Next up was Claude-Marie Vincendon, a petite French-Egyptian, who became Larry’s third wife in 1961.

Claude was lovely and, over the years, Sappho would spend holidays with them in a peasant cottage near Nimes in France, where Larry was writing the Alexandria Quartet which was to make him famous.

According to Sappho, it was when Claude died suddenly from lung cancer in 1967 and Larry was floored by grief, that the relationship between daughter and father darkened.

‘Since Claude died, his traditional pattern of: wife – whore/stupid/bitch: me – virgin/wise has disintegrated. Because none of the women he has had since then ever measured up to Claude, he has been placing more and more the role of wife on me – always aggressive toward wives,’ she wrote. ‘They can’t do anything right expect be sweet and kind and giving.’

Presumably, if there had been any abuse, it would have started around this time.

‘I feel that when I’m with him – or writing to him – that I am on his black side. I’m frightened of him physically and mentally,’ she wrote. ‘My father always lived on a balance of madness – he is an aggressive, demonic drunkard… I never thought he violent until he hit me.’

Damning stuff. But all this was written long after the time and was never documented in Sappho’s contemporaneous diaries.

And poor Sappho had her demons. In 1979, after two abortions in six months, she had a nervous breakdown and it was apparently during psychoanalysis that her first memories of incest bubbled up.

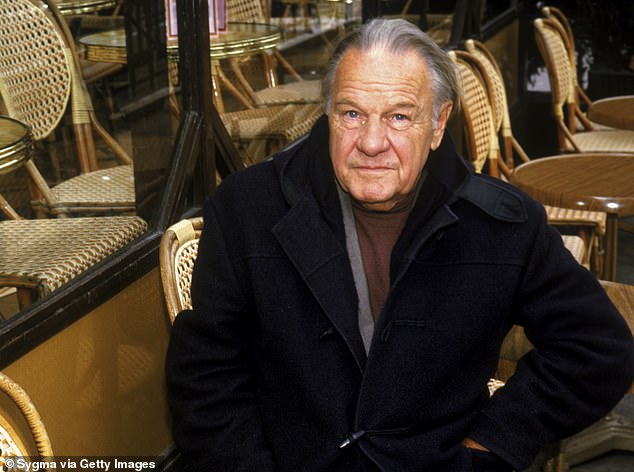

Today – more than 30 years after his death – Larry’s lush, exotic and erotic musings on love, art and the theory of relativity feel overblown, over–written and desperately out of date, writes Jane Fryer

When her allegations were released in 1991 – after Larry’s death at her stipulation – the Durrell family were appalled. Gerald was apparently too angry to speak. Nancy never spoke of it. Ghislaine, whom he had gone on to marry in 1973, was adamant that it had been a normal relationship. The family blamed it all on Sappho’s fragile mental health and wild imagination, and closed ranks.

But those people who believed her pointed to a few possible clues.

That well into her 20s, every letter from him sparked a mixture of excitement and terrible apprehension. Each trip to France made her ill with nervous diarrhoea.

That incest themes ran through some of her father’s works. That her close friends insisted she was not remotely mad.

And that, just before her death, she scribbled on an envelope: ‘In the event that my father should request to be buried with me, my wish is that the request be refused.’

Hard to know the truth.

There seems no doubt that Larry adored his daughter – once boasting that she was ‘simply dazzling for beauty and brains and will be a great poet’.

Perhaps he loved her too much. As with other women in his life, he plundered her life appallingly and, over the years, she found intimate, private details – her affairs, abortions and breakdowns – popping up in the pages of his later books.

Which, sadly for Larry and regardless of however many thousand words he continued to bash out every week, never showed any of his early brilliance.

Today – more than 30 years after his death – his lush, exotic and erotic musings on love, art and the theory of relativity feel overblown, over–written and desperately out of date.

But so does Larry. So perhaps the Durrells’ editorial policy was a good one. Perhaps, despite Haag’s best intentions, it would be better to know less about Larry and the damage he caused as he smashed through other people’s lives.