This article is taken from the July 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £25.

For the producers, it was an obvious project. Peter Benchley’s book about a beach resort menaced by a great white shark had gripped them as they read it. Afterwards, one of them commented that, had they read it a second time, they’d have realised it was unfilmable.

It’s 50 years since Jaws hit cinemas, becoming the first summer blockbuster. Before it was a famous success, it was a famous disaster, a bet on a young director that ran wildly over budget, a project planned around a mechanical model of a monster that was such a mess when the crew tried to film it that it barely appeared in the final movie.

Watching the film now, it can feel overshadowed by Steven Spielberg’s later more confident — and more effects-laden — work. Two of the things that caused Spielberg the most trouble at the time were central to its success. He had insisted on filming on the ocean, a nightmare because the salt water destroyed equipment and it was impossible to stop boats from sailing into the background.

The expected 55-day shoot lasted almost three times that. And he had planned to make much more use of the fake sharks his effects team had built, but they too struggled with the water and looked unconvincing, so he ended up cutting them from much of the film. The result was an unseen menace that was all the more terrifying.

It’s easy to imagine the film that a more sensible director would have made, working in a studio swimming pool. But they would have lost the terrifying sense the film gives us of three men alone in an ocean menaced by a terror only occasionally glimpsed, giving us instead a forgettable gore-fest of munched swimmers.

The film changed Spielberg’s life, and that of another Steven. A teenager in Baton Rouge walked out of the cinema with two questions: “What does ‘directed by’ mean, and who is Steven Spielberg?” This was Steven Soderbergh, who would become one of the most prolific filmmakers of modern times.

The young Soderbergh decided that to learn what a director did, he must study Jaws. He would sit through five showings a day, trying to understand how each part of the film worked.

Soderbergh also achieved early success, with 1989’s Sex, Lies and Videotape. He struggled to follow that up, but found his stride in the late 1990s, with a run that is surely unequalled in the modern era. Between 1998 and 2001 he released Out of Sight, The Limey, Erin Brockovich, Traffic and Ocean’s Eleven. In 2001 he had the distinction of being up against himself for the Best Director Oscar (he lost for Erin Brockovich but won for Traffic).

Whilst Spielberg has released blockbuster after blockbuster, Soderbergh’s career has been more hit and miss, but his misses are better than a lot of other people’s hits.

Matt Hancock was mocked for revealing that he had watched 2011’s Contagion at the start of the pandemic, but the film was remarkable for what it predicted about a global virus, from lockdowns to vaccine competition to vaccine passports. In 2022 Soderbergh released one of the best films dealing with the actual pandemic, Kimi, about a woman who has adapted so well to lockdown that she refuses to leave her apartment.

Somehow, whilst Hollywood now seems only to produce big-budget special effects films where the universe is about to get destroyed, and where you have to have seen four other films and two TV series to understand what’s going on, Soderbergh has found a way to make the kind of film that filled cinemas in the last century: intelligent, under two hours, human stories with a beginning, middle and end.

This year’s spy thriller Black Bag, now streaming, is a perfect example, but if you’re short of something to watch, just see which Soderbergh film is available to you.

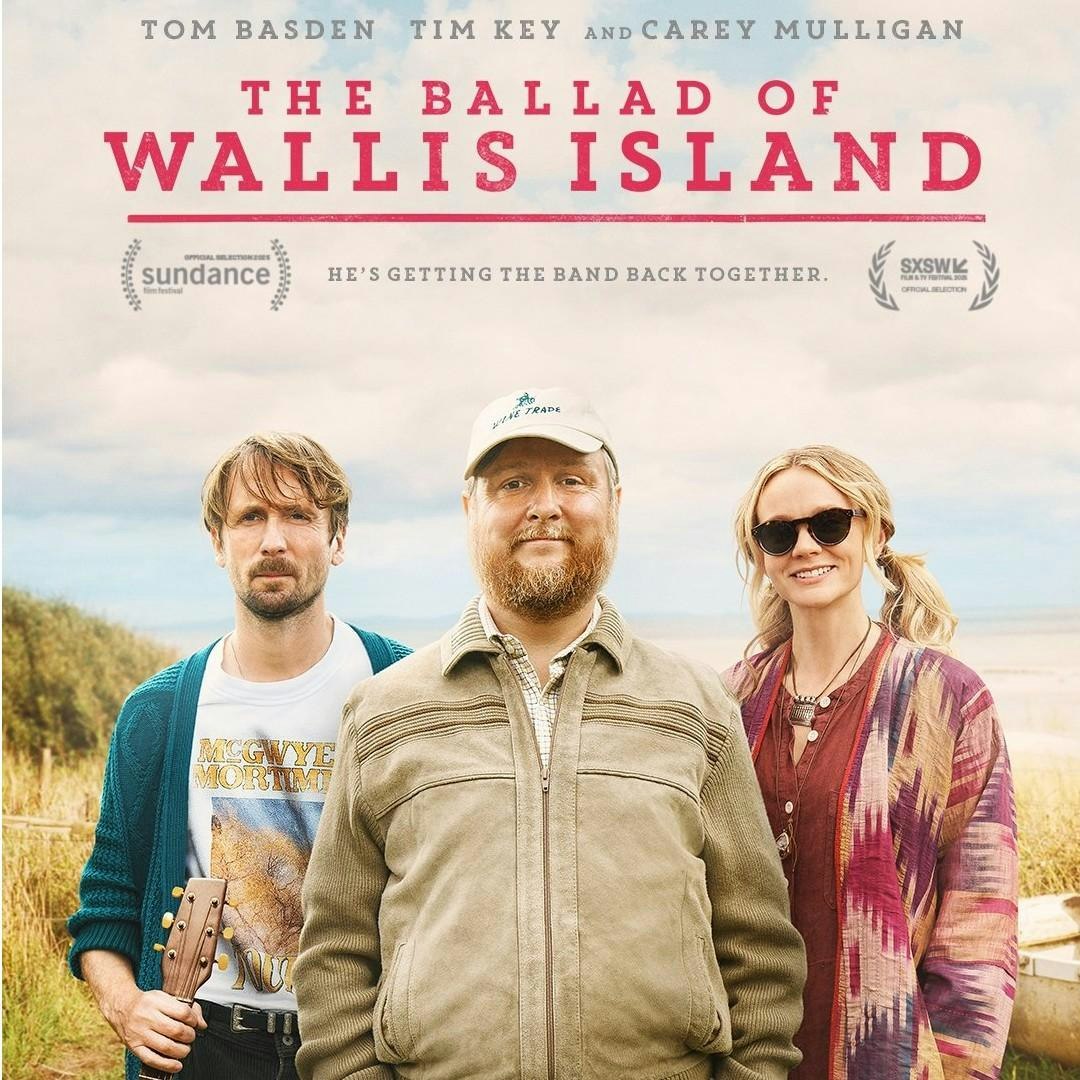

Not one of his but a film that ticks all those boxes, is the delightful British comedy The Ballad of Wallis Island. It ignores trivialities like saving the world and focuses on the big stuff: love, grief, ambition and disappointment.

Tim Key plays Charles, a lottery winner who has decided to spend part of his fortune paying his favourite folk duo to come to the remote Welsh island where he lives and play their first gig together since their acrimonious split a decade earlier.

Tom Basden — who co-wrote the film with Key — and Carey Mulligan are McGwyer and Mortimer, the singers and former lovers with unresolved business.

All the performances are excellent: Key as a man determined to fill every silence with banalities, Basden as an irritable artist who cannot let go of the past and Mulligan as one who has given up on it. I laughed throughout, even as, occasionally, my eyes moistened.

The film has barely touched cinemas, and, by the time you read this, it may well have disappeared, swept aside by modern blockbusters about dragons and dinosaurs and zombies. But it is worth seeking out.

The first blockbuster was superficially a film about a shark, but Spielberg, struggling to get his monster to perform, leant more and more on his actors. And surely the reason that Jaws has lasted is because it’s really about people. In that sense, The Ballad of Wallis Island is its proper heir.