Perhaps the most surprising thing about Norman Tebbit, who has died aged 94, was that in younger days he was a commercial airline pilot.

One expects pilots to be suave personalities, murmuring honeyed reassurance via the intercom and banking the aeroplane into a seamless descent before it touches down with a sough of squishy tyres.

I may be doing Norman a professional injustice – it is possible that in the cockpit he was a model of patient poise – but politically he took a more pulse-quickening approach. He was, in debate, as direct as an agitated hornet. He dived out of the sun, flew low and shattered more than glasshouses with his sonic boom. Tebbit’s politics were, if you like, a question of ‘fasten your seatbelts’. Or even ‘bombs away’.

Unemployed rioters who moaned about their joblessness? They should follow the example of his dad who ‘got on his bike and looked for work’. Muslim women wearing burkas? ‘If they wish to cover their faces and isolate themselves from the rest of the community and so thoroughly reject our culture, then I cannot imagine why they want to be here at all.’

Another target was the BBC. ‘The word ‘conservative’ is used by the BBC as a portmanteau word of abuse for anyone whose views differ from the insufferable, smug, sanctimonious, naive, guilt-ridden, wet, pink orthodoxy of that sunset home of the third-rate minds of that third-rate decade, the 1960s.’ Six runs.

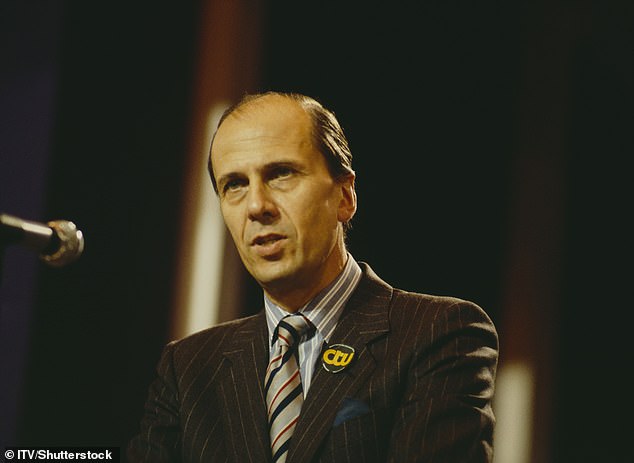

Former Conservative MP Norman Tebbit, who has died at age 94, was, in debate, as direct as an agitated hornet, writes QUENTIN LETTS

Mr Tebbit with Margaret Thatcher, campaigning on the eve of the 1987 general election

Such forthrightness was Norman Tebbit’s political hallmark and it explains why he will be missed. At Westminster today we have few like him. Some of the Reform MPs, such as Lee Anderson and Nigel Farage, may offer occasional echoes of Tebbit, as does Great Yarmouth’s Rupert Lowe and the Conservatives‘ Esther McVey. And for all his dottiness, Jeremy Corbyn at least says what he believes.

In the Lords there is not only Lord Blunkett, a rare voice of common sense, but also the former Tory MP Craig Mackinlay, who lost his limbs to sepsis in 2023 and has returned to Parliament with astonishing resilience.

Mackinlay’s lack of public self-pity calls to mind the stoicism Tebbit showed after the Brighton bomb of 1984, when he and his wife Margaret were so badly hurt.

Their lives were never the same but Norman never made a big to-do about it in public – though he couldn’t forgive the IRA and would have been appalled by the witch-hunt against SAS veterans of the Troubles who now face the threat of prosecution.

He was ahead of his time, a pioneer who foresaw where socialism would lead and predicted the fecklessness of a world of welfare-dependants in which people no longer went out to look for work as his father did. A Britain where, today, about a quarter of the working-age population do not currently have a job.

A cool, spare, pared-back, flinty figure, he was the sort of man you find in the novels of Nevil Shute. Shute’s heroes are modest, uncomplaining, uncomplicated. Alas, like Norman Tebbit and his views of life, Nevil Shute’s books have fallen from fashion. For the moment.

Politics at present is an exercise in vacillation and oscillation. To some extent it probably always was, but these days the falsity is done with greater fanning of faces and fluttering of eyelashes.

In the 35 years or so that I have watched from my Commons press gallery seat, Parliament’s crazy parade has become fuzzier, its language less bracing. Or as Norman might have said, wet.

He was, in private, not hard. He was considerate and could be very funny. But he did not think he had to project a cuddly image to the electorate.

He sensed that voters were grown-up enough to hear politicians express opinions in an unvarnished manner. Today’s parliamentarians filter themselves, hesitating to say what they think. In a bid to be all things to all minorities they use milquetoast euphemisms.

They slip into safe cliches and adopt the matey pose of Jackanory presenters. Obscure, dilute, equivocate: that is the modern approach. It may mean our politicians are not so widely hated but it does mean we hold them in contempt, which is possibly worse.

The Leftist establishment certainly hated Norman Tebbit. At the height of Thatcherism he was the kicking boy of the Guardian, BBC and its chums through Whitehall.

TV’s Spitting Image depicted him as a boot boy in biker leathers and five-o’clock shadow, beating his colleagues’ heads into the Cabinet table. The show benefited from politicians who had sufficient character to turn into a latex cartoon. It is far harder to turn a bore like Sir Keir Starmer into one.

The voters view things the same way. Politicians with strong personas make democratic debate more honest because they force us to confront the arguments and reach a conclusion.

Parliament is about ‘giving voice’ to the kingdom, even if voters’ opinions are spiky. A Parliament that speaks only in consensual inanities, particularly at a time when the public are surging with anger, is failing to do its job.

Norman Tebbit understood that politics is not about being liked but about saying what he thought in a clear, memorable way and hoping enough electors would agree. If you gain a reputation for that, you can get away with the occasional stance they dislike. They will take the view ‘at least you know where you stand with Norman’.

Indeed we did. We knew that he was sceptical of big government, pro self-sufficiency and that he disliked ‘the big, greedy, arrogant, power-mad mobsters calling themselves trade unionists’. Those out-of-control union leaders brought the Labour government to its knees in the 1970s, just as they may do in the 2020s.

Tebbit put his views in a vinegary voice that admitted as little to political image-bending concerns as did his comb-over hairdo. He sometimes used to wear a pinstripe suit, but those Spitting Image biker leathers were truer to the man inside.

A Whitehall permanent secretary said Tebbit was the best Cabinet minister he ever served, such was his clarity of thought and his personal consideration

Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and party chairman Norman Tebbit wave to the crowds from Conservative Central Office, Smith Square, after being elected to a third term of government

And yet a Whitehall permanent secretary I knew said Tebbit was the best Cabinet minister he ever served, such was his clarity of thought and his personal consideration.

Sometimes he overdid it. During one raucous debate he shouted at Labour MP Tom Litterick, who had recently had cardiac troubles: ‘Why don’t you have another heart attack?’

He also had a soft spot for apartheid South Africa that smelled pretty over-ripe to some of us. But was it really racist to suggest he hoped immigrants and their children from the Caribbean and Asia would one day support the England cricket XI?

The Left cried blue murder but was it not, in fact, a decent, prophetic expression of support for multi-ethnic integration, given that last year net immigration to this country amounted to 431,000 people and more than 30,000 asylum seekers are housed in hotels?

Today’s obituaries will chronicle Norman Tebbit’s rise from the lower middle-classes to the peaks of a government that rescued Britain (at least briefly) from socialism.

They will chart his career downs, its more numerous ups and record the dignity he and his family showed in the face of terrorism. He will be depicted, no doubt, as an outlier, an agitator, even a fomenter of trouble. But it is the creamy-voiced establishment consensualists, with their dishonest mirages and suppression of authentic views, that cause division.

MPs should not be scared of disagreement. Sharp debate is entirely proper in public life. We need a Parliament whose members worry less about being liked and who do more to reflect, with as much wizened acidity as Norman Tebbit at his best, the honest views of their compatriots.