Norman Tebbit, who has died aged 94, launched himself into the public consciousness in October 1981 with a phrase that has entered political folklore, as well as dictionaries of quotations.

He was addressing the Tory party conference at a time when the Thatcher government was deeply unpopular and reacted angrily to a suggestion by a Young Conservative that a spate of urban riots the previous summer had been a natural response to the high unemployment of the time.

‘I grew up in the ’30s with an unemployed father,’ Tebbit told party activists. ‘He didn’t riot. He got on his bike and looked for work, and he kept looking for it.’

His remarks were ecstatically received by a party on the defensive during the great economic shake-out of the 1980s. And the response made Margaret Thatcher, who had just promoted Tebbit to the cabinet as Employment Secretary and had long been an admirer of his, realise what a political weapon she had in a man who could speak directly to the instincts of the Tory faithful.

Three years later Tebbit assumed another place in history, though in the most tragic of circumstances. Britain woke up on October 13, 1984, to live television pictures of him and his wife, Margaret, being dug out of the rubble of the Grand Hotel in Brighton following the IRA’s assassination attempt on Mrs Thatcher and her cabinet.

Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and Tory chairman Norman Tebbit on election night in June 1987, when the Conservatives achieved another landslide victory

Five people were killed and 31, including the Tebbits, injured in the blast. Tebbit described his own injuries as akin to the whole of his left side having been ‘sandpapered’. Muscle and flesh were torn away and his pelvis damaged: he walked with a limp for the rest of his life.

Grave though his wounds were, Tebbit was saved from more serious injury by a mattress that protected him from falling rubble. His wife was less fortunate: she suffered horrific spinal injuries that confined her to a wheelchair for the rest of her life. Tebbit’s hatred of the terrorists who had destroyed Margaret’s life, and very nearly taken his, never abated.

During his ministerial career Tebbit was the incarnation of the ‘Essex Man’ phenomenon in the Tory party. Of working-class stock, he embodied the determined, aspirational, self-reliant attitudes that Thatcherism came to be built upon, and which in the 1980s transformed Britain.

Norman Beresford Tebbit was born in Ponders End, Middlesex, on March 29. 1931, and attended a grammar school in Enfield – an education that was the route to the top for so many of his generation. He left school at 16 and found a job as a junior share price researcher on the Financial Times.

In 1949, he was called up for national service, and trained as a pilot in the RAF, flying Meteor and Vampire jets. He narrowly escaped death when trapped in a burning Meteor, having to break the cockpit canopy to get out.

Norman Tebbit is carried away on a stretcher from the Grand Hotel bombing in Brighton in October 1984. The IRA had attempted to assassinate Margaret Thatcher and her cabinet

Norman Tebbit with his wife Margaret, who was left paralysed after the Brighton attack, in 2004. He quit the Cabinet to look after her, and worked hard well into his 70s to pay for her care

After a couple of unsettled years in advertising following his demobilisation in 1951, he used the skills he acquired in the RAF to re-train as an airline pilot, and worked for BOAC from 1953 until 1970.

He also became an official of the British Air Line Pilots’ Association, a fact noted with irony by his critics when, as employment secretary, he was the scourge of the trade unions.

Throughout the 1960s he was active in the Conservative Party, and in 1970 won the seat of Epping in Essex from Labour. He soon felt uncomfortable supporting the government of Edward Heath, and positioned himself on the Right of the party by joining the anti-immigration Monday Club. Unsurprisingly, Heath did not mark him out for promotion, although he did become an unpaid parliamentary private secretary.

His seat was abolished under boundary changes in 1974 and he became the member for Chingford, just to the south of his former seat on the Essex/London border. He held the seat until he left the Commons in 1992 and in time his adversarial approach caused detractors to call him ‘the Chingford Skinhead’.

Once Mrs Thatcher became leader of the Conservative Party in February 1975 Tebbit began an ascent to high office. He soon made a name for himself attacking the excesses of the trade unions – often in the most controversial language.

In late 1975 he rounded on Michael Foot, the then employment secretary, for supporting the sacking of six men for their refusal to join a union, and the denial to them of unemployment benefit. Tebbit accused Foot of ‘pure, undiluted fascism’ and of being ‘a bitter opponent of freedom and liberty’.

Tebbit was howled down by Labour for saying this, but was supported by much of the press. Nearly two years later he returned to the theme, during the notorious Grunwick dispute.

Norman Tebbit at the Conservative Party Conference in 1982, alongside Margaret Thatcher

Grunwick was a photo processing laboratory whose owner, George Ward, refused to recognise trade unions. In retaliation, the unions attempted to close him down. Tebbit was outraged that the shadow employment secretary, Jim Prior, wanted to appease the union.

He spoke of a ‘threat from the Marxist collectivist totalitarians’, and said that those who tried to appease them – including in his own party – shared the morality of the two leading French collaborators with the Nazis, Marshal Petain and Pierre Laval. This outraged the ‘Wets’ in his own party, but boosted Tebbit’s following among the Thatcherites.

When Foot attempted to take a Bill through the Commons that would have made union membership compulsory in many cases, Tebbit accused him again of ‘fascism’. Foot retorted that Tebbit was a ‘semi-housetrained polecat’.

Tebbit’s belligerence, and willingness to pick a fight with his political opponents, won him a place in the government when Mrs Thatcher came to power in May 1979. She appointed him under-secretary for trade.

Mrs Thatcher was so impressed by him that he was promoted in January 1981 to Minister of State in the Department of Industry, and then to the Cabinet as Employment Secretary the following September.

Mrs Thatcher’s main priority in her first term was to drive through reform of the unions – and Jim Prior, Tebbit’s predecessor, had been reluctant to take them on.

Tebbit was more than willing. He introduced a Bill that prohibited closed shops unless 80 per cent of workers supported one and increased compensation for workers dismissed because they would not join one.

Even more controversially, the 1982 Employment Bill made unions liable for civil damages if they incited illegal strikes. Tebbit regarded this Act as his most important achievement in office.

Although this, and Tebbit’s outspoken views on social issues such as morality and immigration made him the darling of the Right, the Left – the ‘Wets’ so disliked by Mrs Thatcher and him – made him into one of their leading hate figures. The worst sort of snobbery was also deployed against him.

The Grand Hotel in Brighton, pictured after the IRA bombing on October 12, 1984

Harold Macmillan, the Old Etonian who was prime minister from 1957 to 1963, said that ‘I heard a chap on the radio this morning talking with a cockney accent. They tell me he is one of Her Majesty’s ministers.’ This snideness betrayed the fact that the old guard in the Tory party were in decline, and Tebbit and those like him were in the ascendant.

After Mrs Thatcher herself, he was the most prominent voice of the party during the 1983 election campaign, making more radio and television appearances than anyone apart from the Prime Minister and a significant contributor to the subsequent landslide victory – the Tories won by 144 seats.

After the election, he replaced his friend Cecil Parkinson as Trade Secretary, when Parkinson resigned over an affair with his secretary.

Mrs Thatcher had wanted to make him Home Secretary – Tebbit was a committed supporter of immigration controls and the restoration of capital punishment. But for these very reasons, Willie Whitelaw – her deputy prime minister – objected vociferously, and Mrs Thatcher did not feel able to go against him.

The injuries Tebbit sustained in the Brighton bomb prevented meant he spent much of 1985 convalescing from his terrible injuries, and coming to terms with having to care for Margaret, who was now paralysed.

Mrs Thatcher wanted to retain him in a senior post but realised that, with everything else he had on his plate, heavy departmental responsibilities were impossible. She made him chairman of the Conservative Party with the sinecure cabinet post of Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, and he was a popular choice with activists at the grass roots whom it was his job to motivate.

The job was, however, anything but straightforward. Early on, Tebbit had to disband the party’s student wing, the Federation of Conservative Students, for publishing an attack in their magazine on Harold Macmillan.

He also began to have differences with Mrs Thatcher. He was unhappy about not being consulted when she gave American bombers permission to fly from British air bases to attack Libya in April 1986.

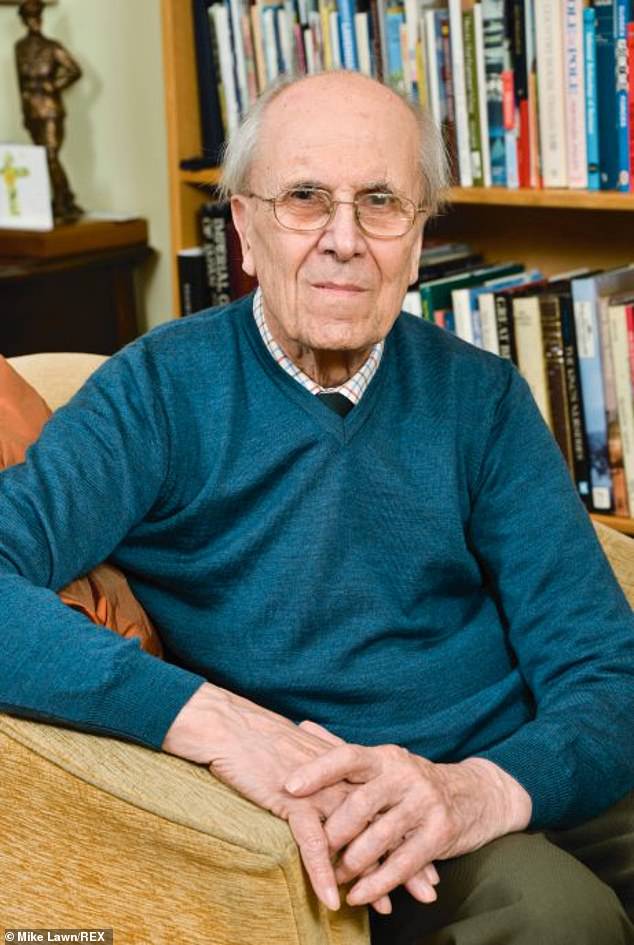

Norman Tebbit in 2014. He was a prominent critic of the coalition government at the time, partly because of what he saw as capitulation to Liberal Democrat policies

He also had to tell her, that month, that the public were becoming tired of her aggressive approach to politics. Polling by Saatchi and Saatchi had identified what they termed ‘the TBW factor’ – standing for ‘That Bloody Woman’. Mrs Thatcher, however, rejected his advice.

Tebbit felt undermined by her decision to use a rival advertising agency to provide her with a second opinion. He did, however, mastermind a successful party conference in October 1986 at Bournemouth under the slogan ‘The Next Move Forward’, which proved the perfect launch pad for the Tories’ third successive election victory in 1987.

However, relations between him and the Prime Minister were strained by the time of the election. She had drafted in another close confidant, Lord Young of Graffham, and his own advisers to help Tebbit in Central Office when it was feared the party’s poll lead was disappearing, and Tebbit bitterly resented the move.

When Tebbit – on what came to be known as ‘Wobbly Thursday’ a week before the election – refused to take Young’s advice, and a poll showed the Tories just two per cent ahead, Young grabbed Tebbit by the lapels and shouted: ‘Norman, listen to me, we’re about to lose this f***ing election.’ The party won a 100-seat majority, but Tebbit had had enough.

He had told the Prime Minister at the start of the campaign that he could not continue in the government after the election, because of his concerns about Margaret. They were devoted to each other, and that devotion only increased after she became disabled.

Despite their disagreements, Mrs Thatcher was deeply reluctant to see him go. She was feeling increasingly isolated, and was dismayed at the loss from her top team of someone who thought so much like her.

Even after he left the cabinet, Tebbit remained a favourite to succeed Mrs Thatcher as leader of the party. However, he knew the job was incompatible with his decision to take a hands-on approach to the care of his wife.

Norman Tebbit is joined by Margaret Thatcher and Cecil Parkinson as he receives a standing ovation after his speech at the Conservative Party Conference in 1981. In 1983, Tebbit replaced Parkinson as Trade Secretary, when Parkinson resigned over an affair with his secretary

Also, Mrs Thatcher allegedly believed that he was too divisive to be elected to the job and, even if he were, he would not be able to win an election as leader.

He caused controversy in 1990 by referring to the ‘cricket test’ for immigrants – he asked whether, when an Indian or West Indian team was playing in England, black or Asian people would cheer for the home team or for their opponents: if the latter, then it was proof they had not integrated.

However, she asked him to return to the Cabinet in November 1990, as education secretary, when Geoffrey Howe resigned, and shortly before her own removal from office. Again, Tebbit cited his wife’s condition as the reason for refusing.

Tebbit remained in the Commons until 1992, when he was elevated to the House of Lords. He attended regularly and continued to take a high-profile role in politics, often not hesitating to lambast subsequent Tory leaders who he felt were insufficiently robust in their policies. In 1995, he backed John Redwood’s leadership bid against John Major.

He wrote a regular column for the Sun and then the Mail on Sunday, which had a popular following for many years, broadcast regularly for Sky and sat on the boards of a number of companies.

He worked hard well into his 70s, principally to put aside the money to pay for Margaret’s care. Friends were generous to them, but the lion’s share of the responsibility for providing for her remained his.

In his later years, Tebbit became more and more hostile to the Tory party of David Cameron. He accused him of planting ‘Blairism’ on the Tory front bench, and said in 2009 that he was voting Ukip in the European elections.

He was a prominent critic of the coalition government of 2010-15, partly because of what he saw as capitulation to Liberal Democrat policies. However, he also questioned David Cameron’s competence and, when the party came under attack for appearing to be run by a social elite, called for it to reconnect with the blue-collar workers who had delivered three victories to Margaret Thatcher.

Tebbit’s somewhat menacing exterior concealed a man of kindness, sensitivity and, above all, loyalty. He carried physical and metaphorical scars from the Brighton bombing to his grave.

But for that, what else Norman Tebbit might have achieved in politics must remain a matter for speculation. The whole course of British history after 1984 might have been radically different. In that sense, while we could quantify the damage the IRA did to Tebbit and his wife, we can never measure the damage it did to the country.