Residents of London will doubtless be disturbed to learn that, as of last Tuesday, 11,000 wanted serious criminals were walking free on the capital’s streets because they hadn’t been tracked down and arrested.

Rapists and robbers, ruthless gang members and drug dealers.

Augmenting that alarming statistic, also at liberty are 5,000 convicted criminals considered sufficiently dangerous to have had their movements restricted by the courts: paedophiles, serial stalkers and the like.

An unusually tall beanpole of a man who appears to be in his late 20s or early 30s, Ahmed (whose name has been changed) is in the former category. Legalities prevent me from revealing his alleged offences, but were he to be tried and found guilty he would face a lengthy jail sentence.

Wandering nonchalantly past Shepherd’s Bush market, in the vibrant heart of west London, in a T-shirt and shorts last Tuesday, the fear that he might be recognised and detained by a passing police officer appears to be the furthest thing from his mind.

His air of complacency is understandable, for the Met’s on-the-ground resources are overstretched, and on the hottest day of the year he seems to have melted into throngs of wilting shoppers and lunching office workers.

Imagine, then, the look of disbelief that crosses Ahmed’s deceptively gentle face when he is surrounded by half a dozen officers, who quickly confirm his wanted status, search and question him, then clap him in handcuffs.

As he stands there, shaking his head from side to side, you can almost see his synapses pulsing. How on earth could they have found me, he seems to be fathoming. Have I been followed? Has someone grassed me up?

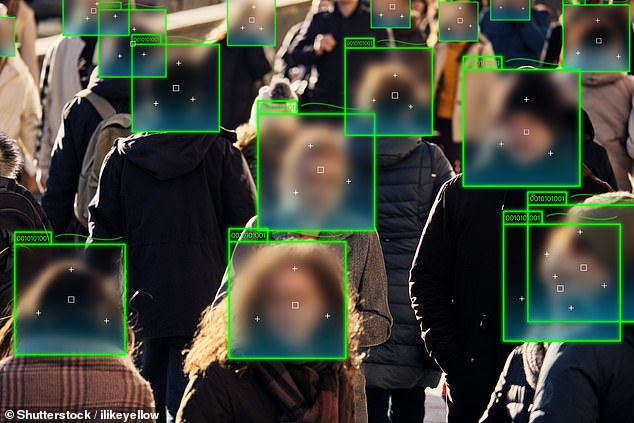

Live facial recognition (LFR) cameras mounted on the pavement are the Met Police’s latest weapon against the 11,000 wanted serious criminals were walking free on the capital’s streets

Ahmed (whose name has been changed) was wandering nonchalantly past Shepherd’s Bush market, in the vibrant heart of west London when he was spotted and quickly arrested

David Jones tested out the cutting-edge technology which is increasingly replacing the need for plodding detective work

He soon learns the truth. In policing, as in other walks of life, cutting-edge technology is increasingly replacing the need for plodding detective work, and as he sauntered along Uxbridge Road, he had been photographed by live facial recognition (LFR) cameras mounted on the pavement.

Almost instantly, his picture was fed into a computer whose biometric software measured his facial features – eyes, nose, mouth – and positively matched his image with one of the above-mentioned 11,000 alleged criminals, named on a ‘watchlist’ drawn up that day by the Met.

This triggered a bleep on the mobile phones of the team of ten officers stationed on the street, ready to make arrests.

Meanwhile, in a nearby police van, a surveillance expert was assessing Ahmed’s profile – name, date of birth, alleged offences, whether he posed a potential danger – and radioing this information to the team. She also watched him on a screen so she could direct the officers swiftly to him.

It was an undeniably slick operation. According to one of the LFR team, on average it takes the Met 17.5 officer hours to track down a suspect by ‘old school’ policing methods; that is, of course, if they are caught at all. Yet, as I saw, Ahmed, a potential danger to the public, had been identified and held in a matter of seconds.

First introduced experimentally in policing almost a decade ago, LFR is being relied on increasingly, not only by the Met, which has pioneered it along with South Wales Police, but by a mounting number of regional forces across the country.

In addition to the streets, it has been deployed at major sporting events such as Six Nations rugby, football matches and F1 races, at pop concerts and even in busy seaside resorts, serving both as a deterrent to crime and a means of identifying and arresting culprits.

In a landmark announcement this week, the Met revealed that LFR had led to more than 1,000 arrests in London (including more than 100 men accused of serious violence towards women and girls) since the start of 2024. Of these, 773 led to charges or cautions.

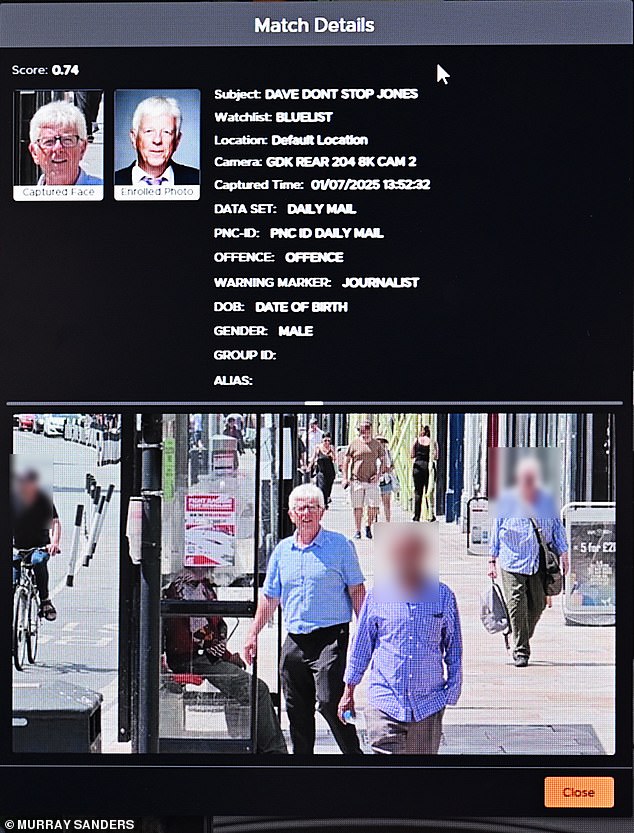

David tested it out for himself and was quickly recognised by the cameras which showed grainy photos of him

Shadow Home Secretary Chris Philp – the MP for Croydon – is very much in favour of the new improvements and David watched the cameras in action as they spotted a criminals who had thus far escaped from the law

Surveillance experts assess potential criminal’s profiles – name, date of birth, alleged offences, whether they pose a potential danger – and radio this information to the team for arrests

And now Met Commissioner Sir Mark Rowley – who has hailed LFR as the most significant investigative advancement since DNA testing – is ready to take a quantum leap towards making it mainstream.

Thus far, the force has deployed only mobile LFR units to crime hotspots, but this summer they will mount their first fixed cameras. Under a pilot scheme, they will be rigged up temporarily on a building (hopefully high enough to be beyond the reach of vandals, unlike many Ulez cameras) in central Croydon, an area plagued in recent years by knife crime.

However, since it means thousands of ordinary citizens are being filmed without their knowledge as they go about their daily lives, and having their photos run through databases, there are inevitably strong concerns in some quarters.

The more so because, as yet, there are no specific laws or regulations governing LFR. In deciding the rights and wrongs of its usage, the courts must turn to human rights, privacy and equality legislation.

Met Commissioner Sir Mark Rowley – who has hailed LFR as the most significant investigative advancement since DNA testing – is ready to take a quantum leap towards making it mainstream

The force has deployed only mobile LFR units to crime hotspots, but this summer they will mount their first fixed cameras in central Croydon

In addition to the streets, it has been deployed at major sporting events such as Six Nations rugby, football matches and F1 races, at pop concerts and even in busy seaside resorts

Decrying it as an intrusion on civil liberties that will have a ‘chilling’ and dystopian effect on society, pressure groups such as Big Brother Watch and Liberty are calling for an outright ban.

They point to scientific studies which have shown that facial recognition technology can unfairly discriminate against black and Asian people, as well as transgender groups and even women.

The reasons for this are complex, but broadly centre on algorithms which can make it more difficult for the system to distinguish between the facial features of people in those categories.

In one grimly ironic case last year, Shaun Thompson, 39, a respected black community worker, was wrongly flagged up as a criminal after being filmed at London Bridge station.

Distressingly held for 30 minutes under threat of arrest, Mr Thompson was actually returning home from Croydon after a voluntary anti-knife crime shift. He is now taking legal action.

However, the likely accuracy of a LFR match is measured by a score, and independent experts say such mistakes are far more likely to occur when the threshold is set at, or below, 0.600 to include a greater number of people.

Mindful of this, the Met uses a threshold of 0.640, which makes such mistakes rare. So much so that, as of last Tuesday, they say, only seven people had been misidentified this year. Against this, 1,042 alerts had proved to be accurate.

Moreover, proponents counterbalance Mr Thompson’s case with another, which shows how facial recognition cameras can be crucial in preventing crime as well as solving it.

There are no specific laws or regulations governing LFR and many have decried it as an intrusion on civil liberties that will have a ‘chilling’ and dystopian effect on society

Thousands of ordinary citizens are being filmed without their knowledge as they go about their daily lives, and having their photos run through databases

Appalled to learn that Essex Police used it to monitor spectators at last year’s Clacton Airshow, Nigel Farage criticised the force, remarking: ‘I don’t want to live in China. I don’t want to be tracked wherever I go.’

In May, paedophile David Cheneler, 73, who has served nine years for child-sex offences, appeared in court for breaching the conditions of an order banning him being alone with a minor.

The court heard how LFR cameras filmed Cheneler walking hand-in-hand with a six-year-old girl, whom he had picked up from school ‘as a favour’ after befriending her mother. When police stopped him, they were a long way from her home and he was hiding a penknife in his belt, but he claimed they had mistakenly ‘caught the wrong bus’.

For breaching the order, he was jailed for two years.

But among dozens of MPs and peers – from across the political spectrum – there remains much scepticism. Appalled to learn that Essex Police used it to monitor spectators at last year’s Clacton Airshow, Nigel Farage criticised the force, remarking: ‘I don’t want to live in China. I don’t want to be tracked wherever I go.’

Other critics range from former Tory Cabinet minister David Davis to Lib Dem leader Sir Ed Davey and socialist Diane Abbott.

Yet Shadow Home Secretary Chris Philp – the MP for Croydon – is very much in favour. Labour’s policing minister Dame Diana Johnson, for her part, has launched a consultation exercise and is expected to set out government plans for the cameras’ use later this year.

It was against this background, and one presumes in the interest of transparency, that the Met allowed me to observe LFR in action last Tuesday afternoon.

I expected the cameras to be hidden from public view, but found them mounted on unmissably tall tripods perched on the pavement.

The Met has two LFR teams, deployed four times a week to hotspots identified from crime data. The rough average is five arrests per five-hour deployment

The biometric software measures 28 facial features which it converts this into digital data and anyone whose features match those of someone on the watchlist, a phone alert sounds (David pictured)

As for the van containing all the gadgetry, that was pillar-box red and also stood out a mile, parked outside a busy Costa Coffee outlet on Uxbridge Road.

Wouldn’t a touch of subterfuge have been more advisable, given that passing criminals might just walk the other way, sharpish?

‘People always ask me why we don’t do this more covertly, but we can’t,’ replied the LFR team leader, a sergeant dressed down in shorts and shades. ‘It would cause ructions. We’ve got so many people criticising this. They think we’re up to all sorts of things. We operate in a way that causes minimum suspicion.’

The Met has two LFR teams, deployed four times a week to hotspots identified from crime data. The rough average is five arrests per five-hour deployment.

When the cameras start rolling, they capture the facial features of everyone who comes within their range – about 20 metres. These are then run through the watchlist.

After the biometric software measures 28 facial features, including the head size, it converts this into digital data, like a human bar-code. Anyone whose features match those of someone on the watchlist to the ‘threshold’ degree of probability sets off the phone alert and is stopped.

Traditional policing kicks in, and a decision must be made on whether to arrest them or simply make checks and send them on their way.

Fugitives trying to evade detection by concealing their faces or wearing disguises should be warned. Recent experiments have proved the latest software capable of matching the facial characteristics of people in surgical masks.

When the cameras start rolling, they capture the facial features of everyone who comes within their range – about 20 metres. These are then run through the watchlist

Fugitives trying to evade detection by concealing their faces or wearing disguises should be warned. Recent experiments have proved the latest software capable of matching the facial characteristics of people in surgical masks

It can also link people with photographs taken decades ago, so the appearance of wrinkles and grey hair is no protection.

(When I was invited to test the system by walking past the camera, it instantly threw up a rock-solid positive match with the grainy press picture I provided).

Bedazzling though all this seems, we are only in the foothills of facial mapping technology.

Already being trialled are infinitely more sensitive systems designed to assess people’s state of mind. When terrorists can be intercepted simply by thinking about detonating a bomb, and would-be murderers can be arrested before drawing their weapon, we really will be in the realms of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four. Except in a very beneficial way.

Back in the here-and-now, another fear voiced by the anti-LFR lobby is that millions of innocent people are having their photos stashed, perhaps for some ulterior purpose.

Nonsense, the LFR team leader insists. Pictures that don’t match up are immediately deleted. Nor is LFR used to monitor climate change protesters and their ilk: another dark claim one hears.

Such assurances cut no ice with Martin, a 50-year-old Shepherd’s Bush musician, who finds it amusing to gurn grotesquely as he passes the camera.

‘I’m a conspiracy theorist and I don’t like the authoritarian nature of this,’ he says. ‘It’s pushing us towards transhumanism and the idea that we all need so be controlled. People wouldn’t have stood for it 20 years ago.’

Glyn Llewelyn, 45, who manages an apartment block plagued by crack addicts, was welcoming of the technology

By 5pm on Tuesday, David had seen two wanted men taken into custody and five other dubious characters, among them a stalker and a risibly self-righteous sex offender warned

Among more than half a dozen local people I spoke to, however, he was a lone protesting voice.

Watching officers dashing to answer another alert – this one set off by a pallid, middle-aged suspect with a Germanic name – one woman let out a cheer.

‘This is amazing! It makes me feel so much safer, having these cameras protecting us,’ the 38-year-old Romanian told me, saying she had escaped an abusive husband with her daughter but feared being found and attacked.

Glyn Llewelyn, 45, who manages an apartment block plagued by crack addicts, was similarly welcoming, as was software developer Mohammed Ukesh, 29 (‘as long as they only use the cameras for crime, not tracking where you are’).

All of which seemed to tally with recent opinion polls, showing around 85 per cent of the London public support the use of LFR.

From all I saw, I’m with them. By 5pm on Tuesday, I had seen two wanted men taken into custody. Five other dubious characters, among them a stalker and a risibly self-righteous sex offender, had received sharp reminders that they were being watched.

Before this technology existed, no-one would have known they were walking among us.

So, be healthily suspicious of these very candid cameras if you must, and yes, let Parliament legislate sensibly on their appropriate use. But surely only those with secrets to hide should fear them?

The rest of us should stop the Big Brother scaremongering and accept them as an ingenious Guardian Angel.