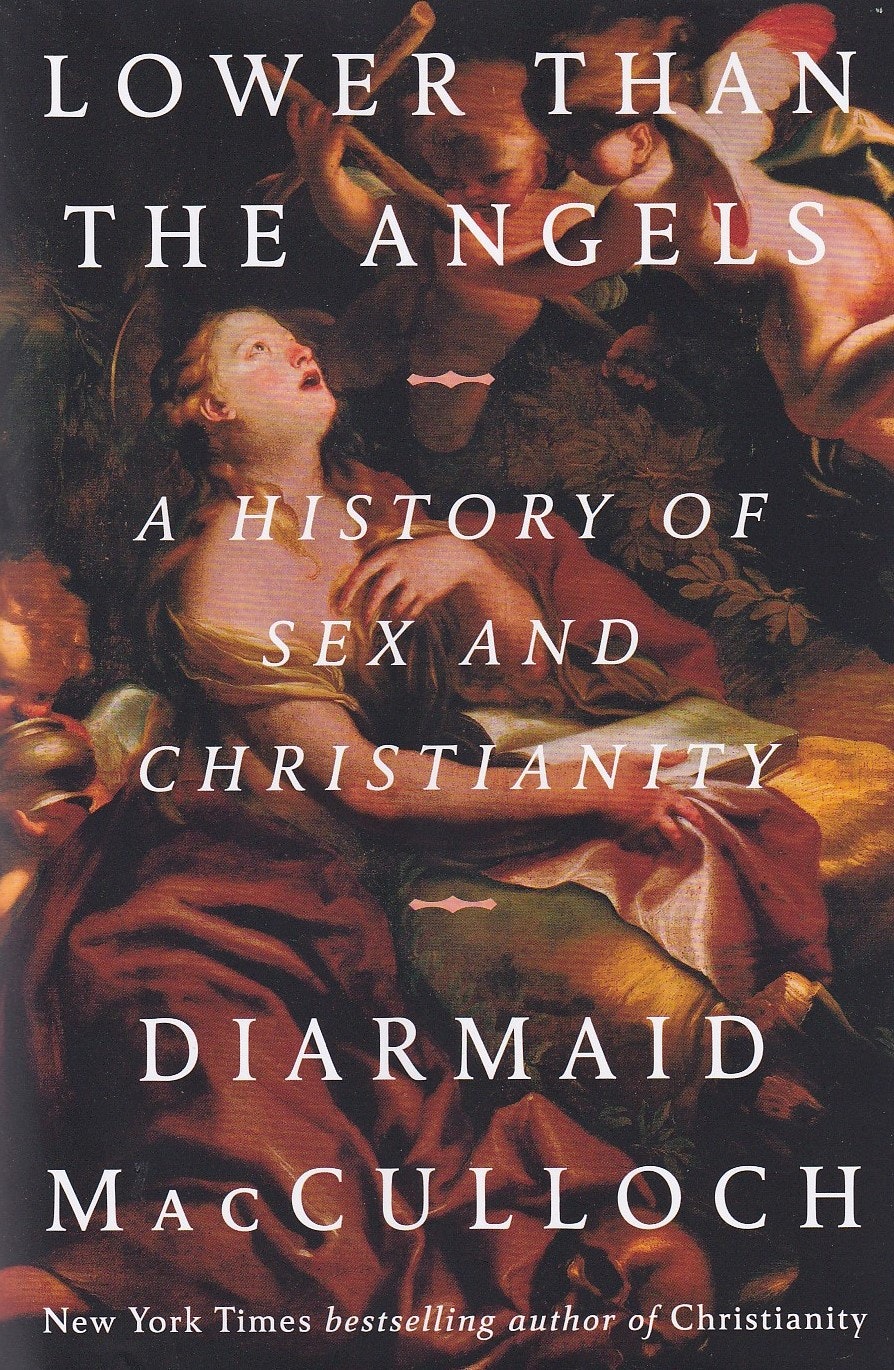

Lower than the Angels: A History of Sex and Christianity

by Diarmaid MacCulloch

(New York & London: Viking, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC, 2024)

ISBN: 9781984878670 (hardback); 9781984878687 (ebook)

xxv + 660 pp., 37 col. & 29 b&w illus.

£35.00

The distinguished author of this ambitious book has published numerous scholarly works on aspects of Christianity and its protagonists. This new tome deals with horny questions of how Christianity has coped with sex, gender, and the family, often with wry asides to lighten the topic, but there is no doubting the author’s deep learning, humanity, wit, and humour (more than apparent in his entertaining lectures) when venturing through the minefields of centuries of bigotry, thin-lipped disapproval, and often cruel punishments meted out to anybody actually enjoying sex, in whatever manifestation.

Confused and confusing Christian attitudes to sex have always struck me as very peculiar. Many years ago, I was amazed when I first saw the extraordinary mortuary chapel of 1647-52 in the church of Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome, commissioned by Cardinal Federigo Cornaro (1579-1653) from Gianlorenzo Bernini (1598-1680), and featuring the marble life-size Ecstasy of St Theresa of Avila (1515-82 — canonised in 1622): of this, the Swiss art-historian, Jacob Christoph Burckhardt (1818-97), celebrated for his writings on the Renaissance in Italy, wrote that “one forgets mere questions of style at the shocking degradation of the supernatural”. In this stunning sculpture, Bernini captured the moment the Saint was pierced by a golden spear in the hands of a smiling, youthful angel which penetrated her very entrails: he depicted her in an attitude of ecstatic abandon, and also alluded to her levitation during the reception of the Eucharist at Mass, a talent possessed by not a few imbued with Southern Saintliness, such as Joseph of Copertino (1603-63), aka “the Flying Friar”. Such a frankly sexual depiction of religious ecstasy should be contrasted with the distinctly repressive flavours that run through much Church teaching. Those flavours are all the more bizarre considering that Christ does not appear to have laid down rules regarding sex, let alone homosexuality, masturbation, or female sexuality, but that has not stopped regiments of guardians of public morals issuing edicts and pronouncements in the name of Christianity, setting up women as spotless virgins or as demoniacally promiscuous whores. It is also very odd that same-sex love could be perceived on the one hand as a sort of link in celibate monastic settings and on the other as a grievous sin to be punished by stoning to death those “passive homosexuals” who, according to luminaries such as St John “Golden-Mouth” Chrysostom (347-407), had forfeited any right to be regarded as male, and should therefore suffer punishment by that method. Chrysostom seems to have been obsessed about sex between men, and indeed shares the dubious distinction with St Peter Damian (1007-72) of having written more about sex than anyone before the advent of Sigmund Freud (1856-1939).

Close relations between older and younger men were very much an accepted part of life in the lands around the Mediterranean: the very deities themselves were no strangers to this, and the connection between the Roman Emperor Hadrian (r.AD 117-138) and the handsome Antinoüs (AD c.111-c.130), is well known. The Bithynian youth’s early death, by suicide or ritual murder, may be connected with the fact that once the younger male grew to full adulthood into his twenties, it was unacceptable for him to continue in his albeit exalted role as the Emperor’s lover, so such a relationship had to end. However, Hadrian had the dead youth deified, and temples dedicated to him were erected in numbers: a new city, Antinoöpolis, on the Nile, was named in his honour. Images of him, however, were sometimes re-cut as females, only the Bithynian hair-do at the back of the head giving the game away.

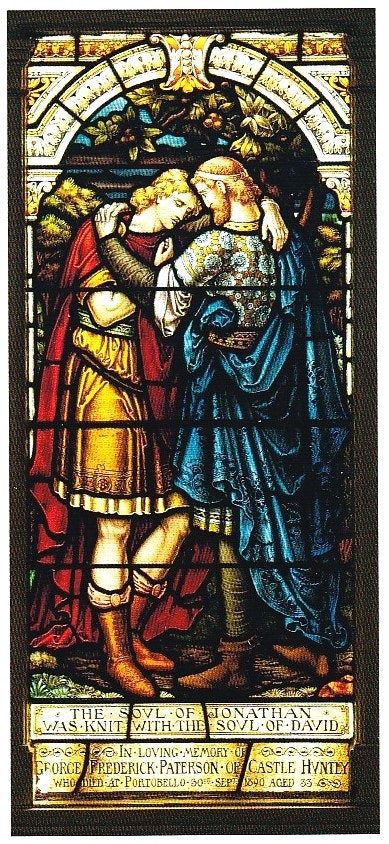

And in Biblical terms, the relationship between David and Jonathan would appear to have been rather more than close, much to the embarrassment of translators and commentators: they would include St Jerome of Strido (c.341-42), who was disapproving of any sexual activity whatsoever, and whose indignation knew no bounds when considering female sexual desire. And there is too the problematic relationship of Christ and the “beloved” disciple: representations do sometimes tend to suggest something very close. The Song of Songs, a celebration of physical love, and none the worse for that, has long been a problem for those prone to become uncomfortably hot beneath their clerical collars as they indulge in intellectual somersaults to prove it is all about something else. The fact is that denunciations by prurient prigs like Chrysostom or Jerome flew in the face of what had been accepted in the ancient world for centuries, and were symptoms of Christianity’s confusions and obsessions concerning sex and its many manifestations which MacCulloch identifies as having stemmed from Hellenistic and Judaic traditions.

One of the more ridiculous examples of how to get into a serious mess and become risible, is the whole question of the Immaculate Conception, and which of Mary’s orifices was actually involved. The eyes, the nose, the mouth, and the ears have all have all been suggested, the last being the most popular since it was through the ear that the angel annunciated the good news. The orifice thought least possible, of course, was the vagina, as the hymen had to be kept intact, even during birth. Such attention to detail has tended to ignore the question of how an incarnate Christ could be male, since his human chromosomes derived entirely from Mary. Chromosomes, however, were not the concern of all those learned scribblers of the past, concerned only to ensure that the BVM’s hymen was intact, which is truly miraculous, given the attested fact in the Gospels that Jesus had several brothers and sisters (or were they half-brothers and half-sisters?). Nevertheless, it seems that many were prompted to physically establish virgo intacta, including the inquisitive Mary Salome, sister or half-sister of the BVM, who suffered thereby.

Unaccountably, MacCulloch shies away from one of the more important threads that influenced the cult of the BVM. I have long insisted that the Nile is as important as the Jordan in the history of Christianity, which emerged, as Norman Douglas (1868-1952) put it, as a “quaint Alexandrian tutti-frutti”, a remark in which there is more than a grain of truth. The civilisation of the West that developed from the Græco-Roman world, from the elaborate organisation of the Christian Church and its close connections with secular power and the legitimising of that power, and from the vast cultural stew of the lands around the Mediterranean Sea, drew heavily on the religion of Ancient Egypt, a fact that is often ignored, glossed over, or claimed as “exaggerated” by commentators. Throughout the Græco-Roman world Egyptian deities were worshipped, and they exercised an enormous influence on other faiths, notably Christianity. It may be this that has led historians (who ought to be objective) to shy away from the obvious. After all, the Gnostics argued that Isis and the Virgin Mary shared the same characteristics, and St Cyril of Alexandria (c.376-444) would have been all too aware of that when he was vigorously promoting the official adoption of the Church of the dogma of Panagia Theotokos, the All-Holy Virgin Mother of God, at the Council of Ephesus in AD 431.

No consideration of Egyptian influences in Europe can afford to ignore Isis, the Great Goddess, Mother of the God, Queen of Heaven, Stella Maris, Navigatrix, etc., who was wise and cunning, infinitely patient, and life-giving, able even to resurrect the dead. Her legacy to European civilisation is immense, and her presence, in attributes and symbols, in religion and philosophy, in architecture, art, and design, and in the Christian Church, is very real. She helped to remove the particularist aspects that had survived in the Christian Church, and, by her femininity and œcumenical appeal, she became loved and revered. She is the key to an understanding of the thread that joins our own time to the distant past, and which explains a great deal within the cultural heritage of the Western European tradition. Furthermore, the resemblances between Isis and the Virgin Mary are far too close and numerous to be accidental. There can, in fact, be no question that the Isiac cult was a profound influence on other religions, not least Christianity. The more we probe the mysterious cult of the goddess Isis, the greater that goddess appears in historical terms: Isis was a familiar deity in the cosmopolitan cities of Rome and Alexandria, in the towns of Pompeii and Herculaneum, in the city-states of the Hellenistic period in Asia Minor, and throughout Gaul. She cannot be ignored or wished out of existence, nor can it be assumed that one day in the fifth century of our era she simply vanished from the hearts and minds of men.

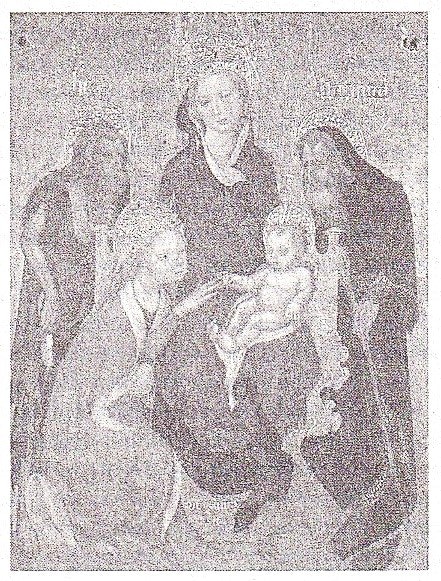

Isis was the ruler of shelter, of heaven, of life: her mighty powers included a unique knowledge of the eternal wisdom of the gods, and she was well-versed in guile. Her tears shed for her murdered brother and consort, Osiris, caused the waters of the Nile to flood, so she was associated with rebirth and with the resurrection of the dead, for the river that seemed to die, like Osiris, was “reborn as the living water”. Every pharaoh was understood to be a reincarnation of Horus, and was therefore the offspring of Isis, the mother-goddess, who could not die, was incorruptible, and was closely involved in the resurrection and re-assembly of the dead. She was the sacred embodiment of motherhood, yet was known as the Great Virgin, an apparent contradiction that will be familiar to Christians. Enthusiasts who have pursued the Marian cultus of the Christian Church, and who are familiar with the works of Hippolytus Marraccius (fl.17th century) and St Alfonso Maria de’ Liguori (1696-1787), will recognise the young heifer as a symbol of the Virgin Mary, whose crescent-moon on many paintings of the post-Counter Reformation period recalls the lunar symbol of the great Egyptian. In imagery Isis is often represented as a comely young woman with cows’ horns on her head-dress, the horns usually framing the globe. The goddess often held in her hands a sceptre of flowers, or one of her breasts and her son, Horus. I have in my possession an ancient tiny amulet showing Isis with Horus in her arms: it is clearly a precursor of the BVM with the infant Jesus.

Osiris, with his sister-wife, enjoyed the most general worship of all the Ancient Egyptian gods. His colour, as that of the god associated with life, was green, and his sacred tree was the evergreen tamarisk. Legend has it that Osiris had ruled as a King, and introduced agriculture, morality, and religion to the world, until his brother Seth cruelly murdered him in a wooden chest, which then was cast into the Nile. The grief-stricken Isis retrieved the chest, but Seth retaliated by cutting the body into small pieces which he then scattered. These parts were collected by Isis, and his body was duly resurrected by her, although the phallus was missing. This obliged the goddess to resort to parthenogenesis in order to conceive and bring forth Horus, avenger of Osiris, and mighty cosmic deity. Another version of the story involves Isis as a kite, fanning the breath of life into Osiris and being impregnated by her ithyphallic but dead brother. In either version the conception of Horus, like that of Jesus, was miraculous. Osiris the Resurrected, the Invincible, possessor of the All-Seeing Eye, was also Ptah, God of Fire and Architect of the Universe, identified with Amun (Ammon), Apollo, Dionysus, the real architect Imhotep, the Apis-Bull, and finally the powerful Græco-Roman Serapis. Later, when the Roman Emperors became gods (nothing less would do after Egypt and its god-like monarchs had been conquered), the precedent of Egypt was powerful, and Isis enjoyed much imperial favour. During the extraordinary fusion of religions in the Ptolemaïc period, Isis and Osiris became further merged with many deities. In particular, Isis, through the range of her powers, grew in stature to be the “most universal of all goddesses”, and held sway over the dominions of heaven, earth, the sea, and (with Serapis) mistress of the Other World beyond. She was the arbiter of life and death, deciding the fate of mortals, and she was the dispenser of “rewards and punishments”. During the first four centuries of our era Isiac cults became established in all parts of the Roman Empire.

Isis and Osiris were usually worshipped near each other, and the same was true of Isis and Serapis. There were the celebrated Ptolemaïc temples of Isis and Osiris at Philæ, and there was a temple of Isis in the Serapeion at Delos, built by the Athenians in about 150 BC. Dedications are known to “Isis, Mother of the God”. The Egyptian goddess, in spite of being identified with Greek deities, was refreshingly different compared with the Olympians, and her qualities appealed to civilised Greeks and Romans who were no longer enamoured of the barbarities and licentiousness of their more traditional deities. She became associated in her capacity as Mistress of the Heavens with the moon, and so became identified with Artemis/Diana. Isis was seen as Pallas Athene, as Persephone, as Demeter, as Aphrodite/Venus, and as Hera. The Egyptian goddess was Queen of earth, of heaven, and of hell. As a moon-goddess she was Artemis/Diana, goddess of chastity, and ruler of the mysteries of childbirth and/or procreative cycles. Her son, Horus, became Apollo himself. Isis, in her catholicity, was astonishing.

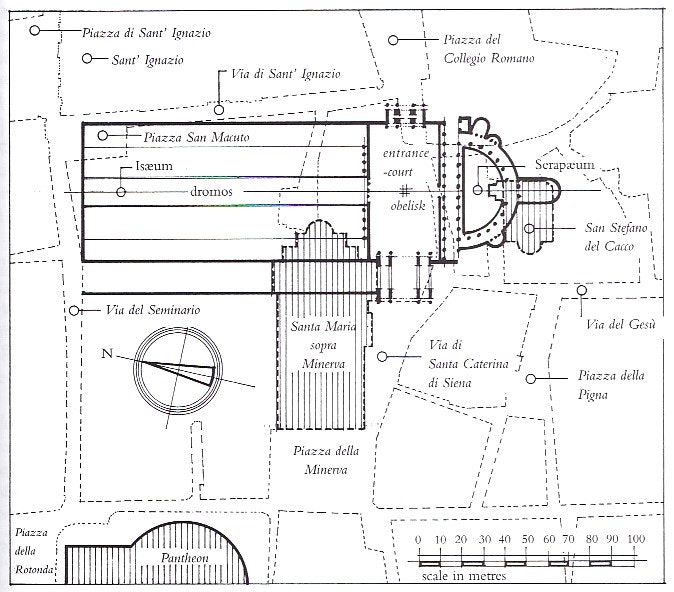

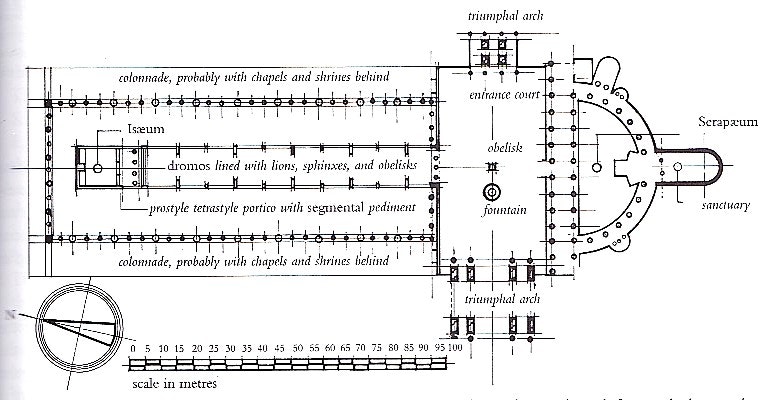

When the Roman Empire established its ascendancy over the ancient land of Egypt, and Roman Emperors followed Hellenistic precedent by identifying with deities, Egyptian custom was absorbed and continued. The apotheosis of the Emperors to the status of gods is clearly linked with the Isiac religion, and when Octavian established the Empire Isis was already well entrenched in Italy. It is clear that, even by the end of the first century AD, Egyptian religion and artefacts permeated the Roman Empire. The numbers of Egyptian and Egyptianising artefacts that survive attest to this, even today: a few hours spent in the Vatican and other great European collections will be sufficient to persuade the most sceptical of how singularly important was Nilotic culture in Antiquity. That inescapable fact, to a very large extent, has been partially suppressed until modern scholarship started to reveal the astounding and widespread prevalence of the devotion to the Nilotic deities that existed at least until the end of the fifth century of our era and, by a process of osmosis, or something very like it, survived, though transmogrified, in ways that are only now beginning to make sense. In particular, it is worth considering the planning of the temples of Isis, often including a Serapæum, which inevitably invites comparison with larger Christian churches that include Lady Chapels, though the genders are reversed. It is a pity that MacCulloch’s book underplays the immense influence the great Egyptian has had on Christianity, but he is not alone by any means on that matter.

As for St Mary Magdalene, she shared her Feast-Day (22 July) with Sts Syntyche of Philippi (fl. 1st century), Plato of Ancyra in Galatia (martyred c.306), Joseph of Tiberias and Scythopolis (d.c.356), Wandregisl of Fontanelle (c.600-68), Meneleus of Messate (d.c.730), and Theophilus the Younger of Constantinople (who met a sticky end in 790). Mary Magdalene has been identified both with Mary, the sister of Martha of Bethany and Lazarus, and with the woman who was a sinner (out of whom Jesus cast seven devils), who anointed Christ’s feet in the house of Simon, stood by the Cross, went to the sepulchre to anoint Christ’s body, and to whom Christ appeared on the morning of Easter Sunday. She appears in the Martyrologium Parvum of the 8th century, and from that time forward her Feast was observed in the West. Her remains were said to have been translated from Ephesus to Constantinople, but she is especially associated with Provence, and her relics were distributed between the former Cluniac church at Vézelay in Burgundy, and Marseilles, among a great many other places professing to possess what amounts to “a host of arms and fingers &c.”, as Sabine Baring-Gould (1834-1924 — whose great work makes admirable bedtime reading), puts it. Her popularity in England, as Patroness of repentant sinners and of the contemplative life, is suggested by nearly two hundred dedications of churches, her ubiquity in mediæval kalendars, and the fact that both Oxford and Cambridge have a College named after her. The Magdalen is usually represented with a vessel of ointment, her hair loose and flowing, but the extraordinary thing about her is her many characters: at one time she was distinctly a “fallen woman”, but recently I read somewhere that she had become transformed into something like “a racy aunt”, which just shows how perceptions can shift with time.

This relatively wholesome Magdalen should not be confused with St Mary Magdalen of Pazzi (1566-1606), whose Feast falls on 25 May, the Carmelite nun beatified by Urban VIII (r.1623-44) and canonised by Clement IX (r.1667-9) in 1669. Some idea of her life may be gleaned from the notes left by Vincenzo Puccini, Confessor to the Convent in Florence, and from the Life written by her Confessor, Virgilius Cepari, SJ (c.1563-1631). She had recurring visions of being in a dismal, horrible swamp populated by the most revolting forms: her head was invaded with ideas of indescribable profanity and sensuality in the place she called her “Den of Lions” where all was desolation, with ghastly, foul imaginings everywhere, and which she inhabited for over five years until one day, when the Sisters were chanting the Te Deum, she rushed to the Prioress, radiant, announcing that the “storm had passed”. She had many visions and ecstasies, conversed with Christ and the Saints (she kept detailed records of those dialogues, which form a significant part of the seven volumes of her writings she left to posterity, edited by F. Nardoni), but for much of the time she was bedridden, suffering “much pain and aridity”, a martyr to violent headaches, hyper-acute sensitivity, and paralysis. These conditions are hardly surprising, given her tendencies to wear little clothing while torturing herself with a crown of thorns, to roll on beds of thorns and barbs, to venture out barefooted in freezing conditions, and to lick the suppurating sores of the diseased, including lepers. Such mortifications of the flesh led to her acquisition of diseased gums, which caused all her teeth to fall out, and her body was covered in putrefying sores which she forbade the other sisters of her Order to cleanse on the grounds that to do so might cause them to experience sexual desire. Her cult was established almost as soon as she died in 1606, centred on her body which is now in the church of the Monastero di Santa Maria Maddelena dei Pazzi, Careggi, Florence.

Unsurprisingly, perhaps, the Pazzi Santa Maria Maddelana was a virgin, whose masochistic-neurotic tendencies were possibly stimulated by her eating habits. Self-macerations, perverted imaginings, cruelty, pruriency, and obsessions about chastity are all inseparably linked with asceticism. And Baroque Saintliness, one observes, is invariably associated with exotic profusions of overdone ornamentation and pointless embellishments of exaggerated virtuousness. What is more, there seems to have been a certain conformity of habit among those who tormented themselves with whips, nails, pins, thorns, etc.; wallowed in ordure; rejoiced in the vermin with whom they shared their fragrant beds; had bodies encrusted in suppurating sores; saw bulimia and anorexia as paths to holiness and as means of seeing visions, and were known to live for a month or more on the sustenance provided by one consecrated wafer; and hated soap and clean clothes, loving dirt, tattered garments, and degradation so as to conform to the unpleasanter ideals of the mendicant friars. These conformists rejoiced in their sufferings, were entirely sexless, antisocial, unclubbable, negations of every masculine or feminine virtue, attaining a level of inanity impressive by any standards. That the cults of asceticism in their more extreme manifestations could lead to such excesses as masochism in the form of torn flesh through self-flagellation or -laceration; see cleanliness as wicked and dirt as virtuous; prefer coprophagy and the licking of pus-filled sores to the consumption of wholesome food as sustenance; and hold up the phantasmagorical stuff of nightmare sufferings as divine literature must be a source of profound alarm, for the state of the minds that promote such illusions can only be questioned. Pious filth indeed.

And how about foreskins? They often feature in the Bible, and one of the more important was that of Christ himself, at least eight examples of which have miraculously survived in Southern Germany alone, one of which I had the privilege of inspecting some time ago, although it was in two small shrivelled pieces, having been broken when being tested for elasticity by an 18th-century cleric with Enlightenment pretensions (his account of the experiment, in crabbed Latin, is hardly a riveting read). This most sacred foreskin also features in the story of St Catherine of Siena (1333 or 1347-80), whose mystic marriage to Christ involved her wearing the prepuce as a wedding-ring. Baring-Gould, however, warned that “great caution” should “be observed in admitting the [startling] visions of ecstatic saints, some of which are peculiarly offensive”. The Bible, in these prissy times, may have to have printed warnings about “emotional upset” on the its first page, as it is stuffed full of violence, sex, death, destruction, plagues, much gnashing of teeth, considerable “smitings”, and whole peoples taken into slavery. But there are also some very unpleasant episodes, such as that reported in Genesis 34:14-31 when the sons of Jacob, having made an arrangement for co-existence with the Hivite Prince Hamor and his son, Shechem, involving circumcision of all the males in the realm, slew those males “when they were sore”, which struck one of my brighter and perceptive former (female) students as “rather unsporting”, and unlikely to endear the Jacobeans to other tribes or groups in the vicinity, or to encourage trust in them.

Female mystics abound in the literature, often using themes of marriage, motherhood, and sex to articulate feelings of divine ecstasy, and those articulations often veer towards the startling, even the distasteful and distinctly embarrassing. One often ponders the psychological makeup of some of the more extreme among them. A 13th-century woman in Vienna, for example, one Agnes Blannbekin (d.1315), had her visions of the 1290s recorded by her confessor, a Franciscan friar: these fevered imaginings include much naked cavortings, among them her own with a similarly nude Christ, and her especial devotions were reserved for the Feast of the Circumcision, when she would experience a hundred times at Mass a sweetness on her tongue as she swallowed the prepuce of Jesus Christ. One is tempted to envisage a kind of variation involving holy fellation. Another female, this time a 14th-century Dominican nun in Switzerland, one Adelheid of Frauenberg, imagined being flayed so that her skin could be fashioned into a nappy for the infant Christ, and she carried things even further by infantilising herself as being suckled by the BVM. MacCulloch writes that “such exuberant female constructions sound suspiciously as if they were testing out the embarrassment thresholds of senior male clergy”, but then an explosive mixture of sexual frustration together with a punitive association of sex with sin and wickedness can do strange things to a psyche.

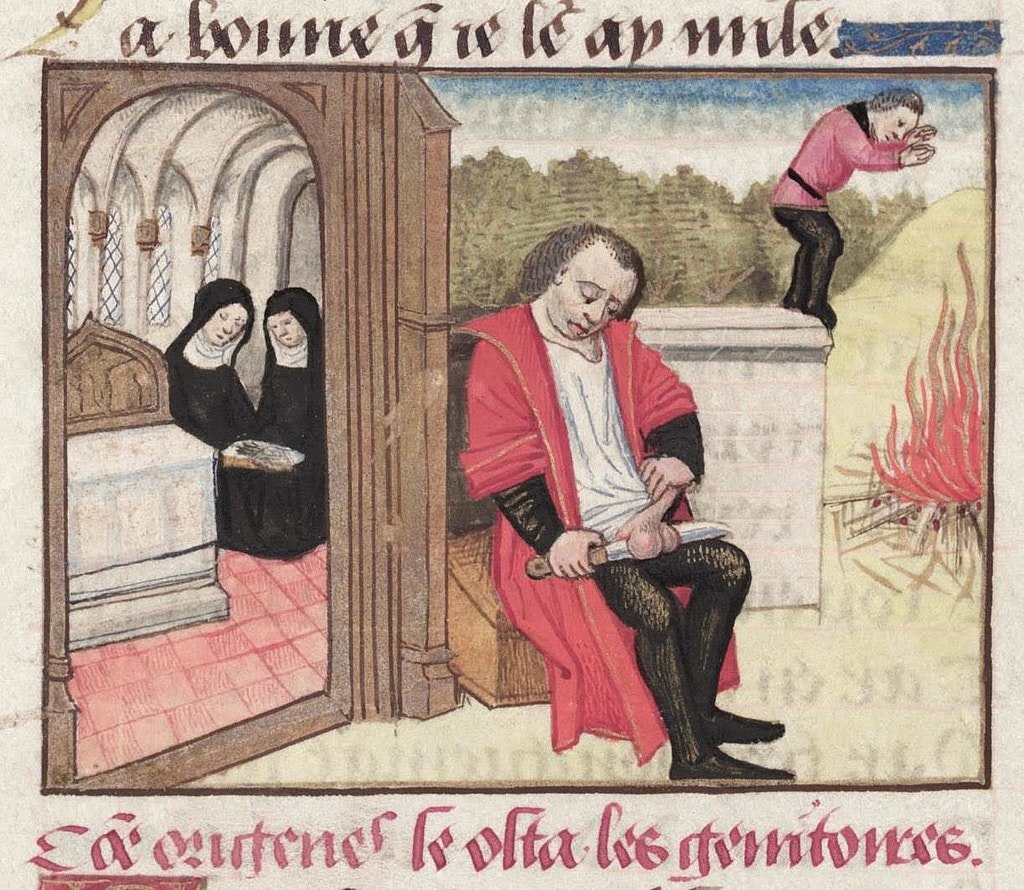

And what of that interesting category of eunuchs, who were so influential in Antiquity, notably in courtly Byzantine circles, as is clear from certain mosaics in the church of San Vitale, Ravenna, where several are depicted, beardless? Angelic gendering, of course, has long been a problem, even though certain angels have indubitably male names (Gabriel, Michael, Raphael), and some were war-like, a kind of Armed Guard in charge of the Heavenly Host, Es erhub sich ein Streit. But from around the fourth century of our era, angels were shown in art as beardless, ‘with pretty-boy good looks’, so were they eunuchs too? Many modern angels, MacCulloch observes, “have lurched towards outright femininity in appearance”, but one wonders, if “we had been indecorous enough to have investigated under” their gorgeous robes, what we might have found? And if humankind had been made “a little lower than the angels” (The Epistle of Paul the Apostle to the Hebrews 2, 7), where does that put angels in terms of sexuality? According to the Book of Jubilees, a Jewish text, perhaps of the second century BC, angels were created with penises already circumcised, but on the whole, angelic maleness “did tiptoe in later centuries towards androgyny”. In these times, when gender fluidity seems to absorb much attention, it is somewhat disconcerting to read in Matthew 19, 12, what Christ had to say: “for there are some eunuchs, which were so born from their mother’s womb: and there are some eunuchs, which were made eunuchs of men: and there are eunuchs, which have made themselves eunuchs for the kingdom of heaven’s sake”. This rather explosive remark perhaps encouraged enthusiasts in search of purity and the dousing of the flames of lust to castrate themselves: Klingsor, in Richard Wagner’s Bühnenweihfestspiel, Parsifal (first performed in 1882), was not alone in taking this somewhat drastic step, for having tried to endure the torture of unbridled longing, the hellish goad of monstrous impulse (Ungebändigten Sehnens Pein, Schrecklichster Triebe Höllendrang), he was compelled to kill off his desires by self-castration. One of the most distinguished theologians of the ancient Church, Origen (c.185-c.253), who sought the liberation of the human spirit from what he perceived as its unnatural union with the sensual, was associated much later with such self-mutilation, although the veracity of that is questionable.

But what such disagreeable manifestations suggest is that what has obsessed the Churches, notably its attitudes to sexuality, have precious little to do with the Scriptures, and virtually nothing in any way linked to what Christ is supposed to have said, but are connected with irrational fears, diseased neuroses, and foul self-interests. Faced with the kind of things mentioned above, the Church seems have moved to attempt to neutralise the fantasies of holy celibates by lauding and promoting The Family, even among the clergy (remembering that “celibate” clergy as a norm came relatively late to Christianity, although there were some who promoted it from the start). In any case, the scandals of recent years suggest that much “celibacy” has been chimærical.

I am always rather leery about using the word “gay” in the sense in which it is largely employed nowadays. In the past it was associated with dissipation and pleasure: someone who was fond of attending public entertainments (known as a “rake”) was called “gay”, but by the 1840s the word was beginning to be applied to women “on the game”, working as prostitutes, although it was also used to suggest someone flashily dressed. It may, through its associations with the 1890s, and therefore with the Oscar Wilde scandal, have begun to take on a connection with homosexuality, probably through prison slang, and seems to have acquired its contemporary meaning more widely during the inter-war period. MacCulloch also uses it sparingly, and wisely, and indeed defines all his terms very clearly. But I wonder if his book, which is really rather wider in scope than its title might suggest, would have been better if reduced and boiled down to more accurately reflect that title, for there is much well-known general history of Christianity within its pages that dilutes some of the more fascinating aspects covered.

I detest endnotes, as the reader has to shuffle back and forth virtually all the time: I do wish publishers would put the notes where they are useful, as footnotes: given that the endnotes in this particular book extend from p.513 to p.605, the sheer effort of looking them up becomes wearisome, and in the end infuriating (some of us actually do want to know where the stuff comes from). The reproduction of the half-tones is also extremely murky (as shown here), and the colour-plates are bunched together between pp.294-5. In short, for such an important book, much more attention should have been given to the design and presentation of the material.

In spite of these quibbles, there is much in this scholarly work to savour and ponder: the concerns and obsessions of two millennia certainly offer enormous scope to any historian worth his salt, and MacCulloch is most certainly worth his. I do wish his publishers had served him much better than they have.