Once hailed as the undisputed king of the British high street, Gerald Ratner was a jeweller with the Midas touch – until a single offhand quip turned his glittering empire to dust.

At his peak in the late 1980s, Ratner was earning £750,000 a year, jetting between his riverside home in Bray, Berks and a Mayfair mansion in a private helicopter, and overseeing a retail empire that controlled half the UK’s jewellery market.

His company, Ratners Group, was the biggest jewellery retailer on earth, owning H. Samuel, Ernest Jones, Leslie Davis and even Watches of Switzerland. In the US alone, he had over a thousand stores.

And yet, it all came crashing down in a matter of days after that infamous speech at the Royal Albert Hall in April 1991.

It was meant to be a bit of harmless banter to liven up the Institute of Directors’ annual convention.

‘We do cut-glass sherry decanters complete with six glasses on a silver-plated tray that your butler can serve you drinks on, all for £4.95,’ he said, gearing up for the hilarious punchline.

‘People say, ‘How can you sell this for such a low price?’. I say, ‘Because it’s total crap’.

‘An M&S prawn sandwich would last longer than most of the earrings the company sold,’ he added, in case they hadn’t got the message.

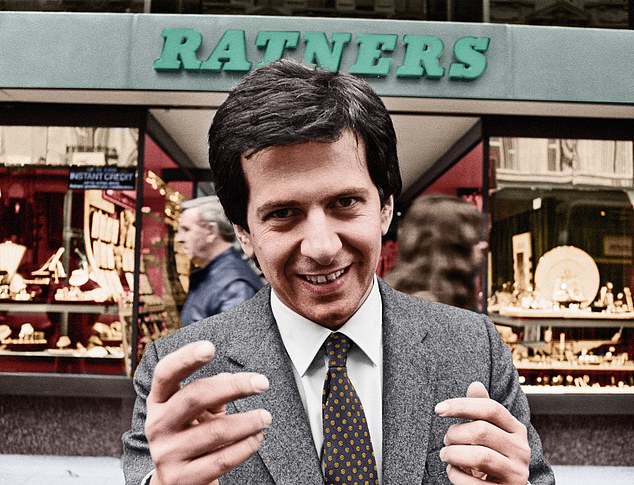

Gerald Ratner (pictured) was a jeweller with the Midas touch – until a single offhand quip turned his glittering empire to dust

British businessman Gerald Ratner is seen outside a branch of Ratners, his chain of High Street jewellers in March 1985

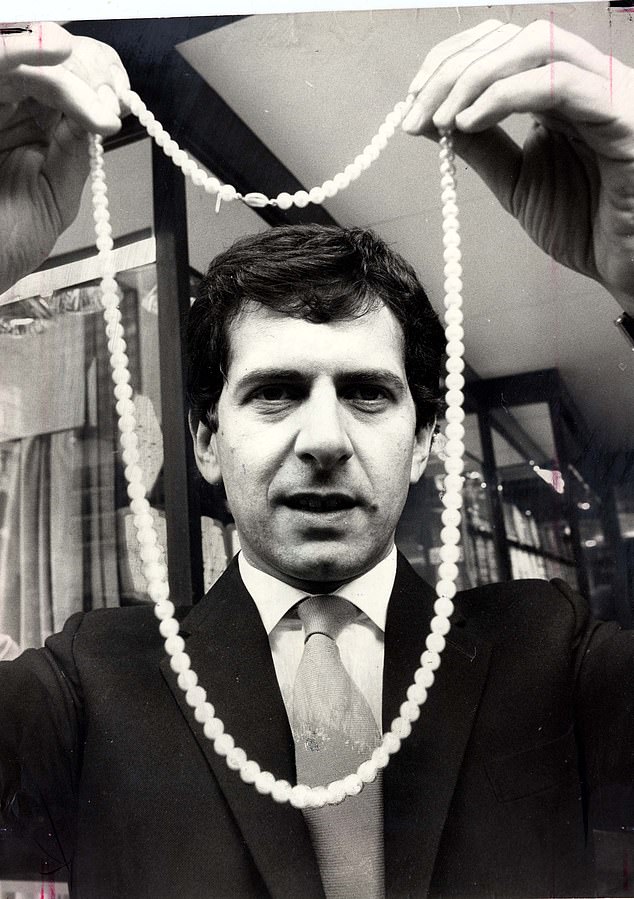

His company, Ratners Group, was the biggest jewellery retailer on earth, owning H. Samuel, Ernest Jones, Leslie Davis and even Watches of Switzerland

In a Britain battered by recession and looking for scapegoats, the nation – and the media – pounced. The name Ratner suddenly became corporate blasphemy.

Overnight, the man who had built a billion-pound brand became a pariah in the City that had once loved him.

More than 34 years on, you might think that a man whose name has become a byword for a catastrophic b****up with the coining of the term, the ‘Ratner effect’, would tire of being constantly reminded of it.

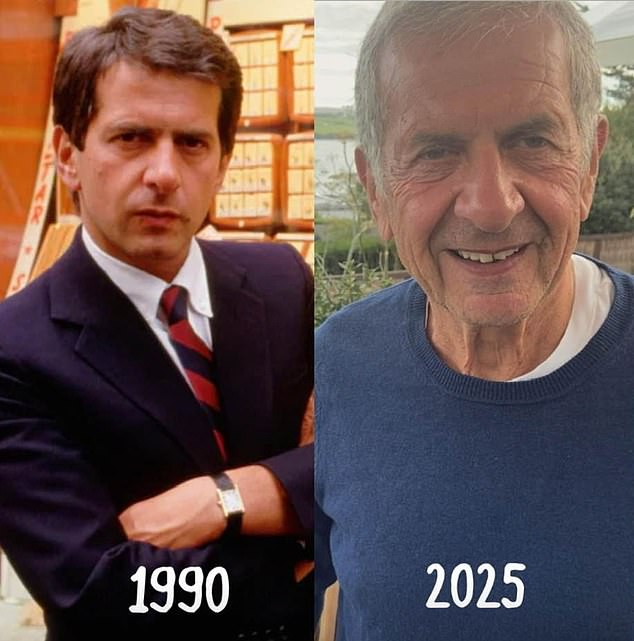

But the reverse is true, as the affable Ratner, now a spritely 75-year-old who cycles 25 miles a day, told MailOnline in an exclusive interview this week.

‘I do motivational speeches about once a week,’ he said. ‘I’m off to Solihull on Saturday. It’s quite cathartic, to be honest.

‘I’m infamous for messing up, but the fact is that I’ve come back and made a success of my life again, so people tell me they find it inspirational, because whatever disaster has befallen them or their business, the chances are it won’t compare to supposedly losing £500million, so it cheers them up.’

Gerald Ratner and his wife Moira are pictured in 2013

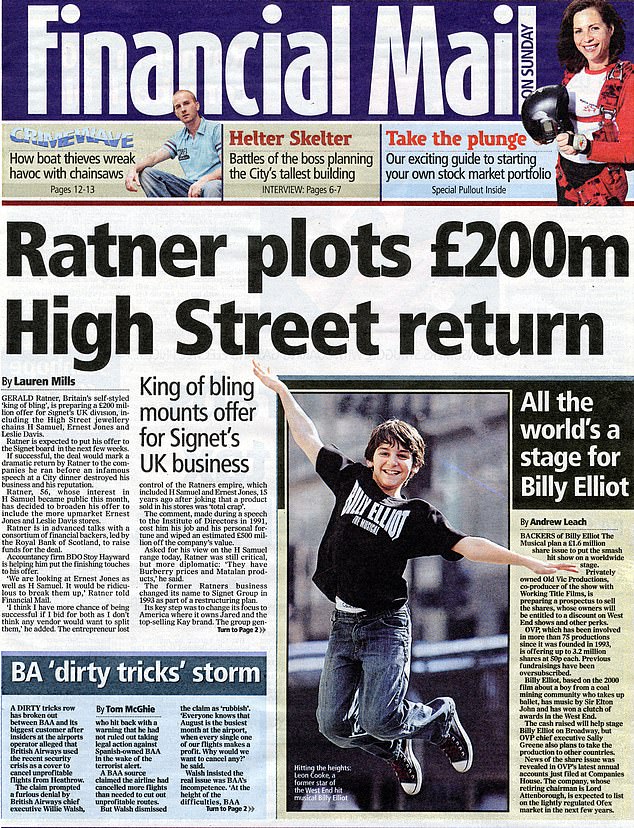

And now, according to a recent report by the Mail on Sunday, Ratner could be on the verge of buying back high street jewellers H Samuel and Ernest Jones from its American owner Signet, but he told us it’s not something he can discuss right now.

It’s all a far cry from his early years. Gerald was expelled from school aged 16 for telling the headmaster at a colleague’s funeral that he might as well stay at the crematorium.

He joined the family business aged 21 as a shop assistant. His father, having battled illness, passed the reins to Gerald in 1984, as Ratners struggled with £34,000 in losses and a looming takeover threat from H. Samuel.

Ratner executed a classic boardroom coup – manipulating both his father and uncles, none of whom spoke to one another, into stepping aside. At just 34, he took control.

His genius was to recognise what few others had: the public didn’t want expensive heirlooms – they wanted affordable, fashionable sparkle. He ripped the doors off the shops, blasted pop music through the aisles, and put flashy gold chains and earrings at the front, where once had sat velvet-ringed solitaire diamonds.

It worked. By the end of the 1980s, Ratners was raking in £1.2bn in turnover a year. Ratner acquired his rivals and revolutionised a dusty industry into a retail juggernaut. ‘At one point, we were taking more money than any other retailer in Europe,’ he boasts.

Then came the spectacular crash.

However much he and others might joke about his downfall these days, there was little to laugh at for him at the time.

Customers boycotted the stores. The company shuttered over 100 branches and laid off swathes of staff. In a desperate bid to shield the firm, Ratner hired a chairman to distance himself from the brand. It didn’t work. He was fired from his own company 18 months later.

By the end of the 1980s, Ratners was raking in £1.2bn in turnover a year. Gerald is pictured in 1991

Businessman Gerald Ratner – the owner of Ratners jewellery company

Gerald Ratner is seen at his Stratton Street Office in 1990

As well as being forced out of the business he and his family had created, he faced a £1m Capital Gains Tax bill for having received share options on shares which were now worthless, having collapsed virtually overnight from £4.20 to just 2p.

‘I basically did nothing for seven years,’ he recalled. ‘I was on anti-depressants, and I’d still be in bed when Countdown came on the telly in the afternoon.’

For years, Ratner drifted aimlessly, but it was exercise that got him going again, in the shape of cycling, after buying a carbon-fibre bicycle.

Then, around the same time, he decided to monetise his own fitness hobby and spotted a disused building in Henley, placing an ad in the Henley Advertiseroffering to waive the joining fee for early sign-ups to his gym – which didn’t actually exist – or belong to him.

Over 800 people registered with direct debits. Ratner marched into his bank, armed with the documents as part of his business plan, and secured a loan to buy the site. Three years later, he sold the business for almost £4 million.

Not only was he back, he’d also realised that infamy could be as valuable a commodity as fame, and launched GeraldOnline, an internet jewellery business that cheekily traded on his name and reputation. ‘I used my notoriety to get free publicity,’ he admits.

At its peak, Gerald was taking in £25 million a year.

Nowadays Ratner and his wife Moira live in a modest but comfortable £1m semi in the commuter town of Wargrave near Reading.

Mr Ratner is seen in 1990 and 2025

Nowadays Ratner (pictured) and his wife Moira live in a modest but comfortable £1m semi in the commuter town of Wargrave near Reading

As he told the Telegraph recently: ‘I read that Bill Gates has 47 bathrooms,’ he shrugs. ‘You don’t need 47 bathrooms. I’ve been there and done that. It doesn’t bring happiness.’

He says he’s happier with his life than he ever was before.

‘I appreciate the little things more – of course you only do that after you’ve lost them.’

In a world where corporate missteps are ruthlessly seized upon, and people are ‘cancelled’ at the drop of a tweet, Ratner’s Riches-to-Rags-to-Riches story serves as both cautionary tale and comeback legend.

He may have once labelled his products ‘crap,’ but there’s nothing cheap about the grit and resilience that saw him turn a national humiliation into a second act few would have dared attempt.

As he said himself: ‘This is part of my motivational speaking thing – If I’d been a politician, I’d have been consigned to history. But in business, if you’re honest about your mistakes – and you learn – there’s always a way back.’