Tuam has come to embody Ireland’s shame. For decades, mothers who had fallen pregnant outside of marriage were sent to the home to give birth and hand their newborns over to the church.

The young women would stay for a year, working for the nuns who ran the institution, before being released once they had ‘paid for their sin’.

Many of their babies however, didn’t make it out alive. Thousands of children died in Ireland’s notorious mother and baby homes, a 2021 enquiry found.

The deaths were hidden from the world, with residents in the quiet town north of Galway unaware for years that as many as 800 babies had been buried at their local home.

‘It was always late in the evening when the burials took place. We never knew what was going on because you couldn’t see over the high walls,’ historian Catherine Corless, who first uncovered the scandal more than ten years ago, told MailOnline.

A baby died almost every fortnight, Corless said, with a damning 1947 report finding that as many as a quarter of the child residents died in a single year.

A recent state-backed commission found the home’s residents lived in ‘appalling physical conditions’, lacking basic sanitary facilities such as running water.

Corless said the children lived in cold, crowded conditions, and only received very limited food. ‘It was pure neglect. They would just give them the bare minimum to keep them alive,’ she said.

The 1947 report also revealed a harrowing picture of life inside the home, with children suffering from malnutrition and in many cases being described as pot-bellied – a sign of starvation.

‘They didn’t care, the illegitimate children didn’t matter,’ Corless said, ‘The final insult to the ones who died was that they placed them in that awful sewage system.’

The St Mary’s mother and baby home in Tuam, Co Galway, was run by the Bon Secours order and demolished years ago

Nuns from the Bessborough Mother and Baby home in Cork, where it is believed that more than 900 babies died

Historian Catherine Corless on the site of the former St Mary’s Mother and Baby Home in Tuam

A general view of the former site of the Bon Secours Mother and Baby home and the memorial garden where it is believed 796 children are buried

The children were buried at first in ‘box coffins’, but were later placed ‘one on top of the other’ in the chambers of a former sewage tank, Corless described.

After a long battle by the local historian, survivors of the home and their families, the site is now being excavated, with many hoping it will finally bring Tuam’s dark past into the open.

Despite growing up in the town and even seeing some of the ‘terrified-looking’ children at her school when she was very young, Corless like many others thought it was just an orphanage, and that ‘the good nuns were looking after all those orphans.’

That was until she began her research in 2011, and discovered that a site many dismissed as a burial ground for famine victims was in fact the final resting place of some of the home’s children.

The mother and baby home, which was run by nuns from the Bon Secours order, was demolished long ago and is now the site of a housing estate and playground.

In 2011, as Corless embarked on a study of the site, she was alerted to a small garden in the area being a possible burial site.

A man who had lived nearby for many years told how his two-storey house allowed him and others to see over the walls.

‘He lived in one of the older houses on the site, they knew that there were burials because the houses had two stories.’

‘He mentioned to me: “There were burials there, did you not know that?” He said he believed they were of the home babies so he brought me over to the site where he thought they were.

Death records obtained by local historian Catherine Corless suggest that children suffered extreme levels of neglect

‘I couldn’t believe it because there was no sign, no headstone, no plaque, absolutely no indication whatsoever there was anyone buried there. I got very curious.’

Corless dug deeper, and soon found that those high walls concealed a litany of other horrors too.

‘The toddlers were just left in rooms with no toys, no stimulation, they had nothing. They were just crying all the time,’ she said.

‘They had no nappies and would spend an awful lot of time sat on potties, which the mothers trained them to do from a very early age.’

She said much of the childcare was left to the women, with only only five nuns running the home which housed as many as 300 babies at any one time.

According to the 1947 report, 34 per cent of children died in the home in 1943, and more than one in four living in the home in 1946, far higher than the average mortality rate at the time.

The home remained open for almost twenty more years after the report was published, while other mother and baby homes stayed open until as late as the 1990s.

Speaking to the Irish Mail on Sunday in 2014, an 85-year-old woman who survived the home in Tuam described the conditions she faced.

The woman, who gave her name only as Mary, spent four years in the home before being placed with a foster family.

She said: ‘I remember going into the home when I was about four. There was a massive hall in it and it was full of young kids running round and they were dirty and cold.

‘There were well over 100 children in there and there were three or four nuns who minded us.

‘The building was very old and we were let out the odd time, but at night the place was absolutely freezing with big stone walls.

‘When we were eating it was in this big long hall and they gave us all this soup out of a big pot, which I remember very well. It was rotten to taste, but it was better than starving.’

She recalled that the children were ‘rarely washed’, and often wore the same clothes for weeks at a time.

‘We were filthy dirty. I remember one time when I soiled myself, the nuns ducked me down into a big cold bath and I never liked nuns after that.’

Work begins on the excavation of the former Bon Secours Mother and Baby Home site

Corless has also recalled her experience as a young girl encountering the ‘home babies’ when they attended her school in the late 1950s and early 60s.

‘I remember the children would come down to the schools hand in hand, a mother at the front and a nun at the back of the line.

‘They were brought to school later and left earlier than us because they were not allowed to mix with children from the town, not allowed to talk to them, not allowed to play with them.’

She said she believes this was done so the children would not ask them about their lives in the home.

‘I remember them being miserable and afraid,’ she said of the children’s physical appearance.

‘They were very skinny, they always had sores of some sort, some of them would have diarrhoea in the classroom and they would have to bring them out.

‘They were really impoverished and always pale. I still remember the terrified look on their faces. They were treated like a species apart from the rest of us.’

As well as the children, the mothers who were shamed and forced into the home also faced mistreatment.

‘They were horrific places,’ Labour MP Liam Conlon, who has long advocated for justice for mother and baby home survivors, told MailOnline.

‘I’ve met survivors from right across Ireland, some of them were in the homes in the 1950s and 60s and some as late as the 90s.

He said the ’emotional and physical abuse’ many experienced there ‘has had a huge impact on every aspect of their lives,’ even to this day.

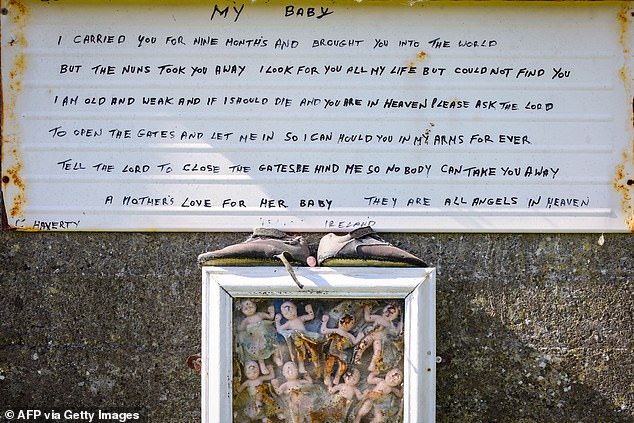

A message left at the site of the former St Mary’s Mother and Baby Home in Tuam, Ireland

‘Women were used as unpaid labour, it was seen as part of their penance. It was often very heavy manual labour.’

While the Tuam mothers worked for ‘very meagre means’, Corless said, ‘money was not scarce’ and the nuns were paid by the state for every mother and child they took in.

‘The mothers did everything, there were lots of jobs to do and each mother had to stay there for a year, work hard and then leave their baby there.

‘They didn’t employ anyone from the town, and that’s how they got away with it, because there was no one to report what was going on,’ Corless said.

‘By working there, the women were paying for their sin. It was horrific. The whole thing was a money racquet.’

Conlon said the separation of mothers and their children also often left both deeply traumatised, with babies often ‘taken off them very soon after birth, adopted abroad and never seen again.’

He said he had also heard testimony from survivors of nuns being ‘very cruel’ and unsupportive when the women gave birth, with many believed to have died in labour.

‘They weren’t supported throughout childbirth complications, it was often seen as a judgement from God,’ Conlon said.

Annette Mckay, who now lives in Manchester, told Sky News how her mother Margaret O’Connor gave birth to a baby at the Tuam home in 1942 after being raped aged 17.

Annette described some of the treatment Maggie endured while being forced to work in the home.

‘My mother worked heavily pregnant, cleaning floors and a nun passing kicked my mother in the stomach.’

A memorial left at the site of the former Mother and Baby institution in Tuam, Co Galway, at the start of pre-excavation works, on June 16, 2025

The little girl died after just six months, with Annette saying her mother recalled how ‘she was pegging washing out and a nun came up behind her and said ‘the child of your sin is dead’.’

She has welcomed the exhumation, saying it will hopefully, at long last, expose the home’s dark secrets.

‘When that place is opened, their dirty, ugly secret, it isn’t a secret anymore. It’s out there.’

Now, with the excavation underway, Corless, the survivors and families of those lost are at last hopeful that there is a light at the end of the tunnel.

‘It’s absolutely wonderful it’s got to this stage,’ Corless said, sharing her approval of the team behind the dig, which is headed by Daniel Macsweeney who has vowed to get ‘every little bone out of that soil.’

‘It’s in good hands, the director said they are focussing on the families first, and what they want,’ she said.

‘I hope this sends a very strong message to Ireland and the world that this can never be allowed to happen again.’

The Bon Secours sisters who ran the home issued an apology and acknowledged that children were buried in a ‘disrespectful and unacceptable way’ in a 2021 statement.

The order said it did ‘not live up’ to its Christian values in its running of the Co Galway facility between 1925 and 1961.

The Irish government also issued an apology in 2021 over the mother and baby home scandal, calling it a ‘dark and shameful chapter’ in Irish history.