There are times in life when you shake yourself hard, as if wishing to awaken from sleep, only to find that the nightmare is all too present and frighteningly real.

So I felt when our representatives in His Majesty’s Government, elected MPs in the country we like to call the ‘Mother of Parliaments’, gave a resounding ‘Yes’ to making it legal for any woman to pop a pill at any time in a pregnancy – and terminate the baby in her womb.

They don’t put it that way, of course. But on Tuesday a free vote in the House of Commons saw hundreds of Labour MPs, including 11 Cabinet ministers, shamefully back a radical change in this country’s abortion laws.

Their vote could well result in mothers giving birth to full-term babies on bathroom floors with no medical help at hand for the vulnerable infants or for the women who procured ‘pills by post’ to give themselves an abortion. All with the blessing of our Government.

It’s horrific. The old, shouty slogan from the 1970s, ‘A Woman’s Right to Choose’, has at last shut down any moral concern that a viable baby has any rights at all.

Here is the key question: why is it called ‘infanticide’ to kill a newborn child, yet legal to end the life of that baby by administering poison when it is fully formed within the womb? Is there a moral difference?

Members voted 379 to 137 to support Labour MP Tonia Antoniazzi’s amendment to the Crime and Policing Bill that will decriminalise abortion. Yet there’s a disturbing contradiction at the heart of the argument.

It will ensure that a woman bringing on her own abortion at any stage in her pregnancy can never be prosecuted even though ‘people providing assistance for late-term abortions for non-medical reasons should still be prosecuted’. So, the mother is above the law.

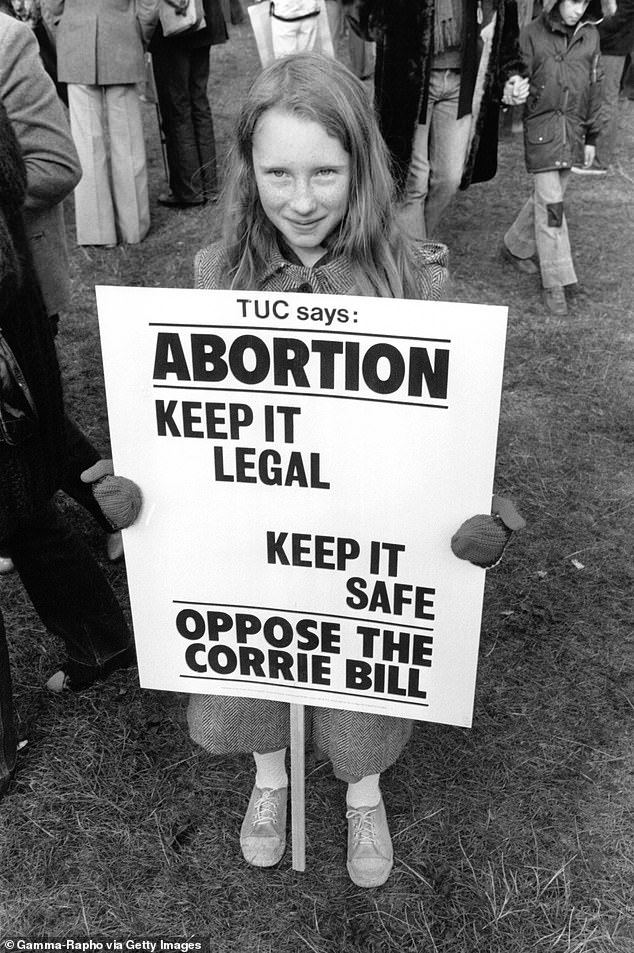

Some of the 80,000 demonstrators taking part in a rally against the 1967 Abortion Act in London’s Hyde Park in 1974

‘Like so many of my feminist peers back in the late 1960s and early 70s, I passionately argued the case for abortion law reform,’ writes Mooney

How on earth does that make sense? It’s morally wrong – and no amount of bleating about women’s ‘ownership over their own bodies’ will ever make it right.

Abortion might be a matter of conscience, but it requires deep public consultation – over time. Where was the lengthy and considered debate on this important issue of ethics? Where were the arguments about the dangers of coercion? The concern for women having abortions with no one there to help?

The revulsion against a viable foetus secretly being wrapped in a towel and put in a rubbish bin? Nowhere.

And was it a part of Labour’s manifesto? No.

Since the majority of public opinion across the UK firmly opposes late abortion, this cavalier government shows itself yet again to be utterly indifferent to something we used to be proud of – democracy.

I should make it clear why I feel so strongly on this issue. Like so many of my feminist peers back in the late 1960s and early 70s, I passionately argued the case for abortion law reform.

We knew how our mothers and grandmothers had feared unwanted pregnancies and what horrors were inflicted by illegal abortionists.

No woman, we proclaimed, should be forced to carry and give birth to an unwanted child. Which is precisely why we celebrated the newly available Pill. Women, we said, should have control over their own bodies.

I still believe we were correct. Nobody in their right mind would want to go back to the dark age of the back-street abortionist – and there will always be regrettable ‘mistakes’.

A foetus at 24 weeks (stock image). Abortion rates are now at an all-time high, with more than 200,000 taking place every year

Yet every movement has its backlash and when I read that the NHS is spending just under £1 million a week on repeat abortions, I find myself plunged into another sort of depression at the sheer carelessness of my own sex.

Yes, some of those terminations will be carried out for sound reasons. I’ve no wish to see babies born to school girls.

And I can honestly say that I’ve never felt sad about having an early termination of my own at the end of 1980.

My son was born in 1974, ‘small for dates’ as they say –at only a fraction of the expected weight – and requiring special care. Then in 1975, I endured 16 hours of labour pushing out a stillborn son at full-term.

In January 1980, I had my daughter prematurely by caesarian section, contracted a dangerous infection –and then heard very bad news from doctors about my poor baby’s multiple health problems.

The prognosis was uncertain and the future looked frightening and exhausting in equal measure – although I had no way of predicting just how hard it would be.

That’s why, at the age of 34, about 11 months after my sick daughter’s birth, I was profoundly relieved to hear my kindly new GP tell me: ‘If you were my daughter I would counsel a termination for medical reasons.’

We’d moved house to give the children a better life in the country near my parents, I’d mislaid my Pills during the chaos and… got unlucky. Knowing what it was like to mourn a dead baby, and then to care for a very sick one, I was very thoughtful – but also determined.

And from that day until this, I have never experienced a single moment of regret about that abortion. It was the right thing to do.

But this is the point: my decision was all about love for the sick daughter who needed maximum attention, it was not primarily about me. It had nothing to do with my so-called ‘right to choose’.

But where were the voices of unselfish care during Tuesday’s vote? How can Labour MPs believe that letting women kill their own babies with impunity represents ‘progressive values’?

One terrible case must be cited here. In 2012, Sarah Catt (then aged 35) was given an eight-year sentence for the full-term abortion of her own baby.

Although Catt already had two children with her husband, that doomed baby was the result of an affair with a work colleague and her husband had no idea about any of it.

She sent to India for the drug and took it at 39 weeks – that is full-term – to cause an early delivery ‘by administering a poison’. Home alone (which must have been awful), she claimed the baby boy was stillborn and that she had buried him. His little body was never found. According to the letter of the law, what happened was not infanticide. But morally that’s exactly what it was.

The absence of a body (for autopsy) made it impossible to prove the case either way, which is surely why Catt refused to reveal where she had buried the child.

The woman never uttered a single word of remorse. So, I ask you, are we supposed to regard her as some sort of desperate victim with ‘rights’?

Presumably all those Labour MPs would say ‘Yes’ – since Tuesday’s vote would mean her callous behaviour was no longer criminal.

We need to remember what role Covid and, more precisely, those destructive lockdowns, played in Tuesday’s vote.

The roll-out of abortion pills-by-post in 2020 – a response to the Covid restrictions – scrapped the protection which was given to women by the former legal obligation to have at least one in-person appointment before being prescribed abortion drugs.

Abortions had to take place in clinics under supervision. It was obviously much safer.

But for the duration of the pandemic, the Conservative government decided to allow women to take abortion pills at home after no more than a telephone call.

The arrangement relied on them not lying about their dates of conception, of course. And some women did lie.

It was supposed to be a temporary measure. But after lockdowns ended, Labour women including Dame Diana Johnson, Stella Creasy and Jess Phillips pushed for the new system to continue. So here we are.

Surely, for the safety of women themselves, we should have returned to the system of in-person appointments before abortion pills could be prescribed.

But MPs have renounced careful argument so that they can grandstand for women’s alleged rights.

Abortion rates are now at an all-time high, with more than 200,000 taking place every year.

Some people (and I count myself among them) would lower the stage in a baby’s development at which an abortion can take place from 24 weeks to 20. For good reason. Imagine a foetus at 24 weeks and you might understand why.

He/she measures about 11in, has clear facial features, eyelashes and eyebrows and, with developed brain activity, can hear sounds.

When it rolls and stretches in the womb the little human being is telling the mother ‘I am here’. Not a collection of cells but a person. A living being capable of independent life. And, surely, a person with human rights?

I know a bit about very tiny babies and the way they can cling to life despite enormous odds. In 2011, a brand new Neonatal Intensive Care Unit opened in Bath after five years of fundraising. As president of the £6.1 million project, I saw first-hand how minuscule, impossibly small babies could survive and thrive under the care and expertise of brilliant staff. Their lives – far more than merely ‘viable’ – were infinitely precious.

What’s more, as founder-patron of Sands (the Stillbirth and Neonatal Society), I have long experience of the grief mothers feel when their babies die just before or just after birth.

This is why we all rejoiced when, in 2024, the Baby Loss certificate Scheme was launched, supported by both Sands and Tommy’s, another key pregnancy and baby loss charity.

This document was, in essence, about respect for the unborn. To date, around 50,000 documents have been issued recognising the significance of miscarriage – the loss of babies early in pregnancy, which is to say before 24 weeks.

The scheme was set up during Rishi Sunak’s government, to (in the words of the Pregnancy Loss review’s co-chair) ‘give all bereaved parents of pre-24-week baby loss the official recognition that their babies did exist and that their babies’ lives, however brief, really do matter.’

You will see where I am going with this.

On the one hand, campaigners fought for the recognition that a non-viable foetus, a collection of cells (as some might say) matters so much it can be mourned as a little human person. And government listens.

On the other hand, different campaigners argued hard for the right of women to abort their own babies at any time at all during pregnancy, even if that collection of cells is a viable baby. And government listens.

There is no case for de-criminalising late-term abortion.

The noble aim of freedom for women must never render a foetus as casually disposable as a used condom.

In no circumstances should we enshrine it in law as a ‘right’.

The widespread revulsion growing against Tuesday’s vote surely lies deep in our DNA since, deep down in mind and heart, we echo an ancient philosophical question when we wonder what life means. Where it begins.

It used to be called ‘quickening’, that first movement the pregnant mother feels, the proof that her unborn child is there, alive (‘quick’) and kicking.

As far back as ancient Greece, people believed this is the moment the foetus becomes ‘animated’ – meaning ‘with soul’.

You don’t hear too much talk about the soul nowadays, do you? But it does no harm to go back to such serious first principles.

I can’t help contrasting that moral truth with the empty rhetoric of here-today-gone-tomorrow MPs who have shamefully failed to recognise that so-called ’empowerment’ for women cannot come at any cost.