Ten days after raids by federal immigration officials in Los Angeles set off a national protest movement, a Hispanic woman walks through the city’s Canoga Park neighborhood. She says she won’t give her name for concern that she might risk trouble for herself or others.

In fact, she won’t say much. But the quiet streets evoke a broader phenomenon sweeping the United States.

“Right now, we’re hiding,” she says, noting that she’s a legal resident in a community where many others do not have government permission to live and work. “We don’t want to stand out.”

Why We Wrote This

The impact of President Donald Trump’s deportation sweep is already being felt as workers stay away from work for fear of arrest. At stake is the future of both individuals and their industries – from farming to construction to restaurants.

As President Donald Trump pursues his promised mass deportation campaign, worksite arrests in both rural areas and big cities are raising questions around the future of the U.S. workforce and its economy, long reliant on immigrants both in and out of lawful status. In one of its latest crackdowns, federal agents said they had arrested 84 unauthorized immigrants on June 17 at the Delta Downs Racetrack near Vinton, Louisiana.

While continuing to target Democratic-led cities, Mr. Trump has also noted that his immigration tactics are “taking very good, longtime workers away” from the farm, hotel, and leisure sectors. It’s unclear what effect, if any, the immigration crackdown has had so far on economic indicators.

But while the impact of President Trump’s deportation sweep may take time to register, uncertainty caused by policy shifts, muscular arrests, and deportations is already taking a toll.

In a series of switchbacks over the past week, the Trump administration first announced ramped-up arrests of unauthorized immigrants, then after some back-and-forth, it told Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to pause arrests at farms, hotels, and restaurants, reported The New York Times. On Sunday, Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins posted on X that she fully supports “deportations of EVERY illegal alien.”

As of this week, the Trump administration has reportedly reversed prior orders to spare farms and other businesses from raids. All this comes as the administration is pushing “self-deportation” and making arrests at sensitive sites like immigration courts.

Worksite raids aren’t new. And even if the administration’s reported goal of 3,000 arrests a day were reached – and those arrests became deportations – the country would fall far short of removing all of America’s estimated 13.7 million unauthorized immigrants in four years.

When high alert becomes a new normal

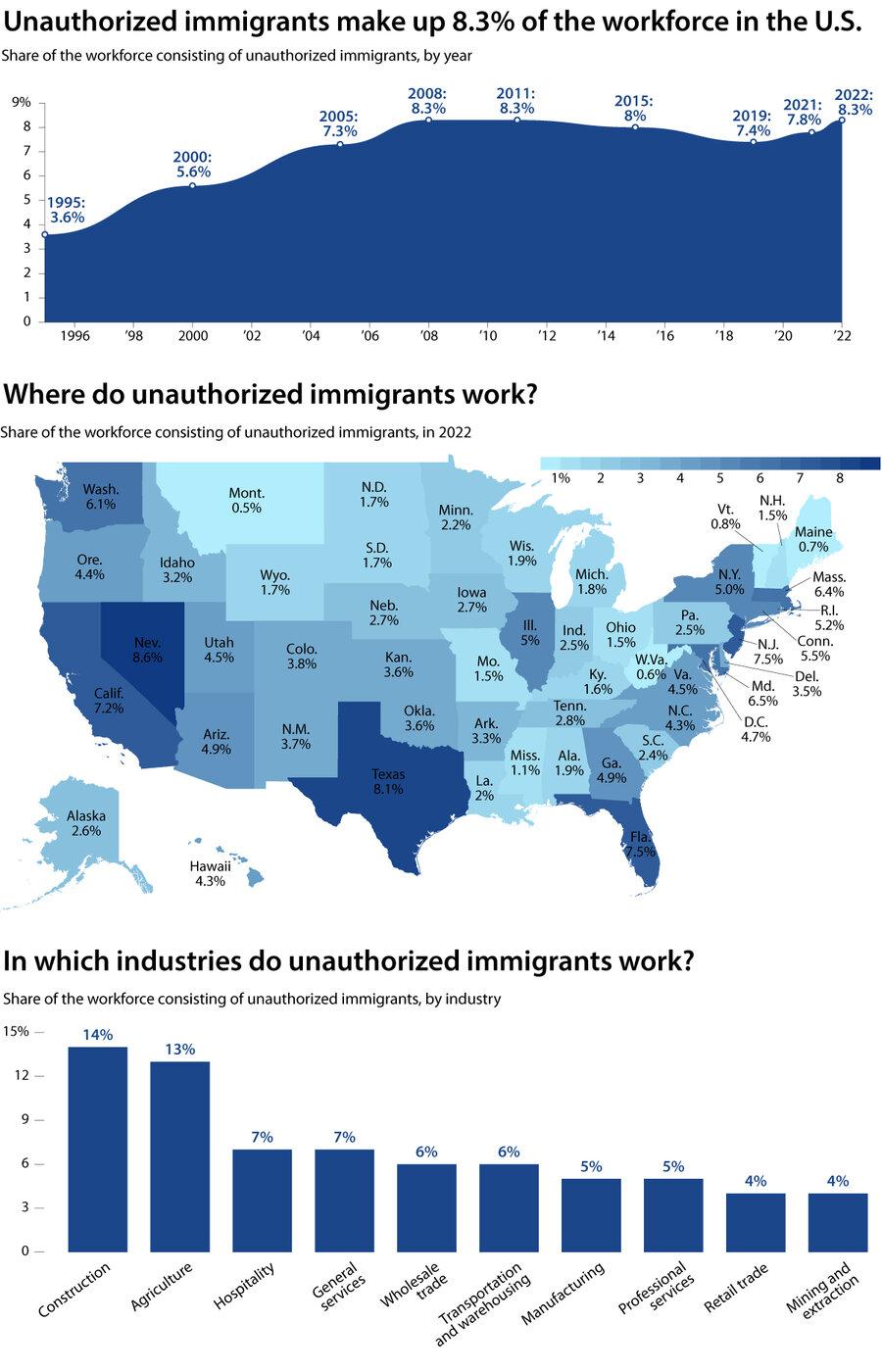

Unauthorized immigrants now make up almost 1 of every 10 U.S. workers, according to the Pew Research Center. More than one-quarter of those are in the construction and agriculture industries. The Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy estimated that unauthorized workers paid $96.7 billion in taxes in 2022, including $19.5 billion in federal income tax. (The total that all Americans paid in federal income taxes in 2022 was $2.1 trillion.)

From the berry fields of Oxnard, California to a meatpacking plant in Omaha, Nebraska, reports of recent targeted worksite arrests have kept immigrants and their advocates on high alert.

In Donna, Texas, farmer Nick Billman now arrives at the fields alone, even though he says his fieldhands have legal work papers. “Zero workers” have shown up since ICE began its latest raids in the Rio Grande Valley, he says.

“What’s happening now is the rumors … that even if you have a work visa or are working on citizenship, you’re going to get rounded up with the rest of them,” says Mr. Billman. “It’s making people sit at home.”

Still, across the country, American employers and immigrant employees have begun speaking up about the broader consequences of mass deportation. Their concerns point to practical issues that the U.S. has long neglected to reconcile, regarding labor markets, border security, and public attitudes on immigration.

“We’ve never really figured out as a nation what to do with nativist sentiment that says we need to restrict immigration – and the reality on the ground, which is that immigrants are doing a lot of work,” says Leticia Saucedo, professor at the University of California, Davis School of Law.

Now, Professor Saucedo says, the administration is grappling with the potential economic impact of Mr. Trump’s deportation goals, which helped reelect him.

Farmers like Robert Dickey, a Republican state representative in Georgia, are some of the strongest supporters of the GOP agenda.

So far, Representative Dickey’s workers who are here on seasonal work visas are showing up at his orchards and timber stands. But that, he understands, could change.

“It’s essential that we make our agriculture industry competitive,” he says. To do that, “You’ve got to have this workforce.”

Where policy meets the punch clock

His conundrum is part of a “sustainability question” as the unique skills and work ethic of immigrant labor are meeting key demands in the U.S. economy, says Austin Kocher, an immigration enforcement expert at Syracuse University in New York.

The whiplash of the last few days, Professor Kocher says, “illustrates the tension within the White House itself about how to approach immigration enforcement policy when you have Republican supporters who are business owners, working class people, construction workers … [working against] pressure from the Stephen Miller and Tom Homan wing, who are saying, ‘Deport everyone.’”

Modern worksite enforcement can be traced back to 1986, when President Ronald Reagan signed the Immigration Reform and Control Act. It outlined what would become a major immigration legacy for the Republican president: allowing an estimated 3 million people to gain legal status.

The act introduced civil and criminal penalties for employers who knowingly hired unauthorized workers. Separately, it’s illegal for immigrants to use false documents for work. Issues with the document verification process, however, have contributed to the ongoing hiring of unauthorized immigrants.

While the Trump White House has often criticized the Biden administration for historic highs in illegal border crossings, many have been here for decades. Unauthorized immigrants made up 3.3% of the total U.S. population as of 2022, according to the Pew Research Center.

“Worksite enforcement remains a cornerstone of our efforts to safeguard public safety, national security and economic stability,” said Tricia McLaughlin, assistant secretary for public affairs with the Department of Homeland Security, in an email to the Monitor.

Worksite raids can be useful for broader enforcement, supporters say. Jerry Robinette, a former official for ICE’s Homeland Security Investigations under the George W. Bush and Obama administrations, said past crackdowns on large companies have led to hundreds of arrests, but also a “voluntary response from a lot of industry wanting to self-disclose … to avoid an ICE HSI investigation of their company and their employees.”

So far, it’s unclear how often unauthorized immigrants are avoiding going to work, a step that jeopardizes their ability to support their families.

President Trump says he has urged ICE to conduct raids in larger, “sanctuary” cities like Los Angeles, Chicago, and New York.

When workers don’t return to work

But that is not keeping raids from “resonating to all parts of the immigrant community,” says Andrew Stettner, director of Economy and Jobs at The Century Foundation, an independent think tank in Washington.

“Usually [ICE will carry out raids] just enough to push people underground and take bad wages,” he says. “But they will ultimately stay here, and the economy will function. We’re now pushing past that. We’re going into unprecedented territory.”

While research suggests that immigrants provide a net benefit to the economy, analysts also note that prior immigrants and native-born workers qualified for low-skill jobs are most likely to face negative wage effects from immigration. Meanwhile, some immigrants are exploited under a system that tacitly accepts large populations of unauthorized people.

Gilberto Alvarez, for now, is an employer who is left holding down the fort. The manager of a Denny’s restaurant south of Los Angeles, he has watched those whom he believes to be federal agents gather in his parking lot. Employees were scared, he says. Some took the week off and have yet to return to work.

Mr. Alvarez and the other managers are picking up the slack, and the restaurant will be OK for a few months, he says, if he manages it properly. But if this goes on for longer, he’ll be “in a bad spot.”

However, some immigration enforcement experts argue that partial slowdowns or increased pressure from agricultural or hospitality interests could influence the administration’s future actions.

Representative Dickey, the central Georgia peach farmer, recently met with Agriculture Secretary Rollins during a trip to Washington to lobby for hurricane relief aid and a long-term solution for immigrant labor.

“The administration hasn’t done anything to hurt us yet, but we’re hoping they can do something to help,” he says.

Los Angeles, which once welcomed Orfelinda Martinez with open arms, is now a place where spotters keep an eye out for immigration agents.

Ms. Martinez sought asylum 30 years ago from Guatemala. Today, she is a U.S. citizen living with her sister just north of Los Angeles.

The people in her community are mostly immigrants, and mostly Hispanic. They work at the nearby ranches, or as landscapers, babysitters, housekeepers, restaurant workers, or construction workers.

Her immigration experience years ago was positive, she says. The officer who worked with her on citizenship “treated me like family,” she says. Still, she keeps risks to a minimum these days, like others in her community. Even though she’s here legally, she says, “If we don’t have to go out, we don’t go out. Just in case.”

It’s not just their future, but also the labor market in bedrock industries, that hangs in the balance.