The wooden cabin in the remote Welsh mountains was packed with hulking blokes sitting silently on bunks with our kit taking up whatever space was left. It was filled with the stink made by men living at close quarters. It was also bitterly cold, the coldest winter anybody could remember. And yet there was nowhere else I’d rather be. Because here I was, at last, on a selection exercise for the SAS.

I was about to discover if I had what it took to be one of Britain’s elite soldiers.

I’d been dreaming of this moment and this opportunity for years. Growing up in working-class Stoke-on-Trent, the black son of a Jamaican father and a white English mother, from a toddler all I’d wanted to be was a soldier. I joined up at 16 and instantly loved everything about the army – the skills I was taught, the way we were challenged both physically and mentally.

Some people hated going out on exercises, especially when it was cold and wet. Not me. The colder and wetter the better. As soon as one exercise had finished, I couldn’t wait for the next to begin. And, having often gone hungry as a child, I loved getting three proper hot meals a day.

Over the next 13 years I rose to the rank of sergeant in the Staffordshire Regiment with front-line service under my belt in Northern Ireland and Iraq. But, encouraged by officers who thought I had leadership qualities, Special Forces was where I saw myself, though now I was actually on the course I realised straight away that making the cut was going to be tougher than I ever imagined.

I was surrounded by lads from all over the military speaking with completely different accents to mine. Some were the red berets of the Paras, others the green berets of the Royal Marines. You could see them congregating together and dismissing those of us from the regular army as ‘craphats’. They looked down on us, irrespective of how hard our own training had been, and the fact that people like me had actually fought in the Gulf.

Most of them looked stronger and fitter than me. Many were so huge their shoulders brushed against the door frame when they entered a room. They looked as if they could walk all day with a house on their back.

I began to feel a prickle of doubt. Do I really belong here?

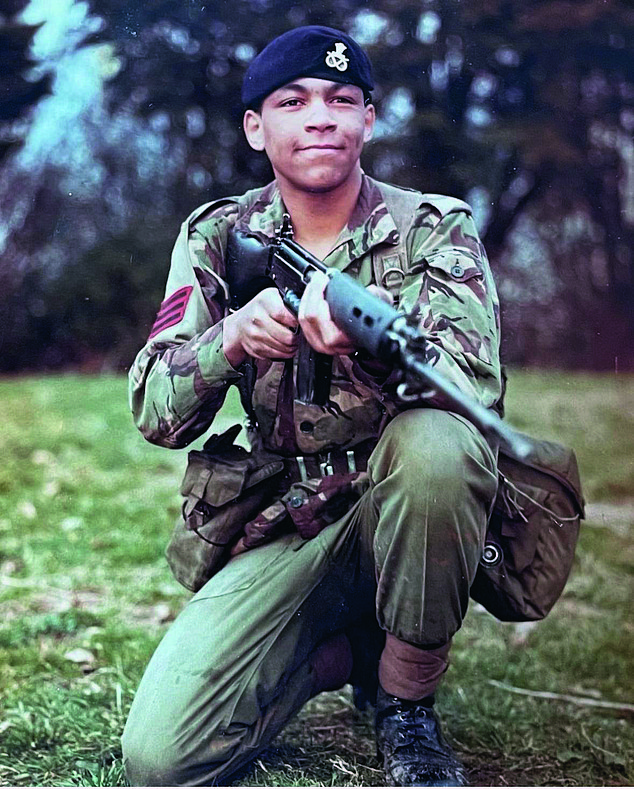

Melvyn Downes realised that making the cut for Special Forces would be tougher than he ever imagined

And I felt even more out of my depth when the man sleeping above me, an officer, launched into a conversation with one of his mates, another officer, using words I wasn’t familiar with and mentioning people and places I’d never heard of. It was all ‘What university were you at again, Charles?’ and ‘Did you know Piers at Sandhurst?’

They possessed that unshakeable sense of confidence shared by lots of people from their background. I was left feeling stupid and unsure of myself. Why did I ever think that a council estate kid like me could even pretend to have a place on a course like this? Plus, I was the only black man. Perhaps I should save myself the agony of carrying on, only to be dumped, and throw in the towel now.

But that’s never been my way. I’ve learned over the years that it’s always better to try and fail rather than fail to try. If you don’t challenge yourself, you’ll never find out what you’re actually capable of.

And so it began, setting off each morning on a route march with heavily weighted packs on our backs. Things started slowly, with nothing too challenging in the early stages.

Yet even after the first day, back at the hut, one of the bunks was empty. Someone had been sent back to his regiment.

The demands on us quickly accelerated. We’d stumbled out into the early morning where vehicles were waiting to take us to the day’s starting point. There we’d be shown a grid reference to memorise and then set off into the wind and rain, pushing and pushing for nine or ten hours a day.

We covered miles and miles of marshes, mud, climbs up hills and scrambles down them. We crossed streams that had been turned into icy rivers by biblical quantities of rain. Most of the time it was dark, and even during the day your eyes were constantly being stabbed by the wind and rain.

We weren’t using the normal paths – at best there would be a trail used by sheep – so you could never trust the terrain. One moment you’d be scrabbling on loose shingle, the next up to your waist in frozen water. There was always an urgency about everything because we never knew how long we had to complete any given task.

Melvyn Downes served in Iraq before applying to join the SAS

You couldn’t afford to rest or slow down because that might be the difference between passing and failing.

I made it my business to run every part I could, stopping only occasionally, and for no more than a minute at a time, to drink and eat. Some times I found myself so hungry and weak that I felt dizzy, and I’d cram a couple of Mars bars down my throat until I felt energy surging back through me. OK, I’d then say to myself, time to pick the pace up again.

But I could feel exhaustion and a thousand tiny niggles building up inside me. I was developing trench foot because dry, clean socks had become a dreamed of but unobtainable luxury.

You had to keep your weapon constantly at arm’s length so you knew exactly where it was at all times, and what state it was in. Is there a bullet in the chamber? Is the safety on? We had to learn quickly – to navigate by the stars, for example, rather than waste time constantly referring to the map and compass.

You weren’t told when you were going to finish, so, as you arrived wet and exhausted at a checkpoint, you didn’t know whether you would be told to get into the vehicle to be taken back to camp or given another grid reference and sent back out.

Some evenings you’d get to what you thought was the final checkpoint, only to be sent on to another one and you’d have to keep going for the whole night, your exhaustion mounting to the point of feeling delirious.

Very quickly this was becoming the hardest physical thing I’d ever done, sapping my strength and pushing me to my limits.

And yet it was more than that. Otherwise, all the massive gym bunnies on the course would still have been here.

Mr Downes had a tough childhood, sometimes going hungry. Pictured with his mother and brother

I found that I had to access some part of my psyche I don’t think I knew existed until then. It was hard to explain what exactly it was, and why I had it while others who were bigger and tougher than me didn’t. Whatever it was that made you want success on this course so much that you were willing to almost break your body to achieve it.

This was what dragged you out of bed on those mornings when you huddled between your sheets listening to rain and sleet pummelling the hut’s window and thought, I cannot go out there. It kept me moving forward, forward, forward even when I was crawling along a rock face on my hands and knees, knowing that if I stood, the wind might actually hurl me over the edge. Even when I was stumbling because I was so tired. Even though my back was a mass of sores and my feet were a red, ragged mess.

I tried to take small steps. I’d focus on just getting through to the end of the day, or through the next hour, or just to the next spindly tree on the horizon. Whatever I needed at that precise moment. If you can break big tasks up into little sections, then nothing’s ever too big to swallow.

One of the hardest things was psychological. In the regular army somebody always tells you if you are doing a good or a bad job, probably by shouting in your face. There was none of that on this course. No praise, no criticism. Nobody raised their voices to us, or smiled in encouragement. The instructors would tell us what they wanted us to do, then let us get on with it.

They made it clear that they did not care whether we succeeded or failed. When you reached a checkpoint, they didn’t even tell you if you’d made it in time. You were just given a new grid reference to commit to memory – we weren’t allowed to write anything down – then away you’d go.

Pain was a constant companion. It wasn’t long before my toenails blackened, then fell off. There wasn’t much time to sleep. And even once you had got into your bed, it wasn’t easy to nod off. Despite my exhaustion my mind would always be racing, and my body throbbing with pain. I never woke feeling rested. The other constant was the knowledge of how easily everything we had worked for could be derailed by a tiny moment of carelessness, or just bad luck. After a couple of weeks, our hut was beginning to empty out. Each night we’d return and there would be one or two fewer men in their beds.

A few had to leave because of serious injuries, like a broken leg. Mostly, though, they’d pulled out of their own accord, a voluntary withdrawal (VW). There’s no shame or recrimination. Nobody tries to change your mind. You go back to your regiment, rightly, with your head held high. But those who remained would get little bumps of surprise when you found out who had gone. ‘Him? Wow. Really?’

You could quit at any time. Halfway through a route march. As you sat in the back of a vehicle waiting to go, cold and damp seeping deep into your bones. A couple of lads simply refused to get out of their beds. Two weeks in, just getting your body to move in the morning became a battle in its own right.

And the thought of quitting was always there, like a devil on your shoulder, filling your mind with promises of clean sheets, hot baths, an end to the pain and exhaustion. There’s nothing stopping you.

I joined up at 16 and instantly loved everything about the army – the skills I was taught, the way we were challenged

I was holding these thoughts at bay, but it was becoming harder and harder. Seeing other blokes VW spurred me on. I was the council-estate kid desperate to prove he was as good as anybody else, that he belonged here. But how long could I keep it up?

One night a couple of weeks in I was lying on my bunk and listening to conversations going on around me.

Five blokes from a regiment down south had their backs turned to me as they looked at a map and speculated about the following day’s route. I padded across to join them. ‘Hi, guys.’ They turned to stare at me – five unfriendly pairs of eyes suddenly trained on me. ‘Could I look at that please?’ I asked, gesturing at the map.

There were a couple of seconds of silence, then one of them, a big man with a gringo moustache and cropped black hair, just said, ‘c**n,’ a vile racial slur, then turned his head away.

The others sniggered.

Anger surged into every part of my body. I couldn’t let this go. I imagined the satisfaction of feeling my knuckles smash into the big bloke’s jaw. That would show them. I felt my hand balling into a fist. I went to take a step forward.

And then I caught myself and stopped. If I got into a scrap, whatever the outcome, that would be the end of my chances of passing selection. I’d be booted off straight away. I forced myself to return to my bunk, where I lay, as they carried on giggling and casting mocking glances in my direction.

I told myself there’s no way in a million years I’m leaving this course before any of you. I will die before I let that happen. Instantly I felt better. The anger at what had been said, and my regret at not having given in to the temptation to lamp the big bastard who’d said it, did not go away. They stayed inside me, simmering. But the heat they produced became energy I could use whenever my inspiration and will to carry on felt depleted.

It also gave me a simple target. My overall goal remained passing selection, but remaining on the course for longer than every single one of those men offered me something closer and more immediately achievable to aim for.

Within a couple of days, I noticed that two of them were gone. I passed one on the hills, moving so slowly it was almost as if he was going backwards. I thought, he isn’t going to make it, and pushed on, a new spring in my step.

For the handful of us who were still left on the course, everything now got even harder. The instructors stopped giving us proper maps to help us navigate – we had to make do with sketches. The distances to cover got longer, and we were expected to complete them faster. For the final endurance test we had to cover well over 60 kilometres of punishing terrain in less than 24 hours, carrying more weight than ever before on our backs.

One morning I came perilously close to being terminated. I had been slipping and sliding through valleys and gulleys, then up onto higher ground, before I arrived at the foot of a mountain. I looked up to the peak, which was shrouded by fog and clouds.

It was really steep but there was no way of traversing it. I’d have to go straight up. I was glad I couldn’t see the summit. If I’d known the full scale of what faced me, I might have lost heart.

I put one foot ahead of me and felt the soles of my boots struggle to get any purchase on the icy rocks. Another step, another struggle. I looked up again, began to calculate how long I’d need to make the ascent, and immediately wished I hadn’t. The top didn’t seem to be any closer than when I started. I found myself beginning to topple, lurching about like a pig at a skating rink, and with my weapon cradled in my arms, I had no easy way of regaining my balance. I shifted my weight and regained control. There was no time to dwell on how close I had come to falling. A voice inside me kept repeating: move, move, move. Slowly, unsteadily, I crawled higher and higher on my hands and knees until, after 45 painful minutes, my limbs coursing with lactic acid and screaming for a rest, every part of me numbed by the cold, I reached the top.

I slipped my pack off my aching shoulders, wincing briefly from newly formed blisters, and sat on it. I had to take a breather. I sat there, my mind scrubbed almost blank by fatigue.

After five minutes I hauled myself up again, cursing. Why am I putting myself through this? There was a stab of pain as I hoisted my pack, then, as I shifted my weight, I cursed again. My injured calf felt as if it was on fire.

I’d balanced my weapon carefully on a rock. And I moved forward to pick it up. As I did so, my right boot caught the butt and sent it spinning down the ice and screed. I watched helplessly as it tumbled further and further away before landing 30 metres down the sheer slope I’d struggled so hard to climb.

I heard a ragged, anguished voice shout, ‘You are effing kidding,’ then realised it was me. I hated the idea that something so stupid could end my attempt to pass selection. That I’d been beaten, not by the course, or by a body that had given up, but by my dumb, clumsy right foot.

Suddenly hating everything and everyone, I scrambled down the slope. Every step, every foothold, felt treacherous. Finally, though, I was close enough to reach out and pick the weapon up, only for my right leg to stride forward, acting with a momentum of its own, and send it bumping down the rock face. It was 60 metres away.

I felt weak and dizzy. Was this actually happening? There was a hot stab of panic as I took stock of my reserves of mental and physical strength. I had little of either left, but I heard that little voice again. Move, move, move. And I did. Weapon recovered and off to the next checkpoint. But it had been a close call.

And as the end came in sight I was still there, along with a few green and red berets, and a scattering of blokes from the regular army. For our final challenge, we were flown to a tropical jungle. Everything there was draining. If you move, you sweat. If you stay still, you sweat.

Your body becomes so clogged up that prickly heat spreads across it. You wake up and find leeches stuck to your feet. Everyone gets worms. You stink, really stink, as does everybody around you. But I loved the challenge and the way the jungle supercharged you senses.

And it was here that I saw off the big cockney guy with the moustache who’d called me a ‘c**n’. About two weeks after we got there, I saw him walk past me on his way to the helicopter pad, his head down.

I gave him a little smile. I was still there.

I’d made it through to the last phase of the course – escape and evasion and resistance to interrogation. I was one of the lucky ones. Or was I? Because what came next would be infinitely worse than I could ever imagine.

- Adapted from Unbreakable by Melvyn Downes (Ebury Spotlight, £22), published on 12th June. © Melvyn Downes 2025. To order a copy for £19.80 (Offer valid to 21/06/25; UK P&P free on orders over £25) go to www.mailshop.co.uk/books or call 020 3176 2937.